Roger Tregear

Enabler 1: Process Architecture

The 7Enablers of BPM describe how process-based management reimagines the theory and practice of management. The first of these enablers, process architecture, is discussed in this paper.

A process architecture is a hierarchical model of the business processes of an organization. It provides a powerful visualization and management tool. Organizations are traditionally managed via the template laid out by the organization chart. Yet not one of the entities shown on any organization chart can, by itself, deliver value to an external customer. The reality is that we create, accumulate, and deliver value through collaboration across the organization chart. We manage resources vertically using the organization chart. We create and deliver value horizontally across the organization, and the key management artifact should be the process architecture. New and important insights are provided into the development and use of a process architecture. Drawing on both theoretical concepts and practical case studies, the paper illustrates an innovative, comprehensive, and effective approach to organization performance management.

A process architecture is a hierarchical model of the processes of an organization. Usually created, initially at least, to include the two or three highest levels, the process architecture provides a powerful visualization and management tool. The process architecture includes not just the hierarchical description of process activities, but also the related resources, documentation, performance measures, measurement methods, and governance arrangements.

This paper describes the purpose, creation, maintenance, and use of a process architecture in reimagining the management of contemporary organizations.

What you can expect to get from the paper

This paper will provide new insights into the development and use of a business process architecture and how this forms the key artifact in the process-centric view of management. The paper draws on both theoretical concepts and practical case studies to illustrate an innovative, comprehensive, and effective approach to organization performance management. Having considered the contents of this paper, the reader will be able to:

- understand the purpose and use of a process architecture

- see the relationship between strategy and business processes

- confirm how business processes operationalize the strategy

- create practical documentation for all to use in operating the value pathways

- prepare for the challenges of creating a process architecture

- improve the management of organizational performance

- focus on what really matters—the creation, accumulation, and delivery of value (products and services) to customers and other stakeholders.

What is a process architecture?

There are many architectures, and many definitions of many architectures, so it is as well to firstly define what is meant by process architecture in this paper.

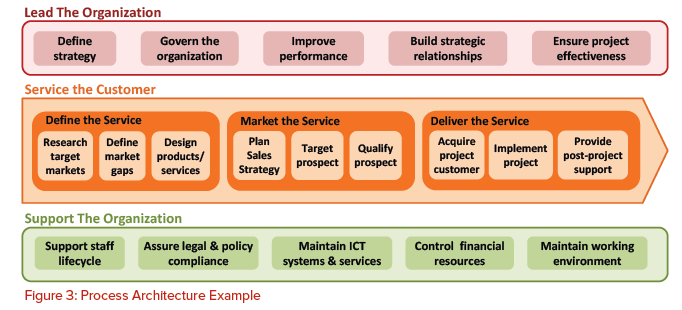

A process architecture is a hierarchical model of the business processes of an organization. Usually created, initially at least, to include the two or three highest levels, the process architecture provides a powerful visualization and management tool. The terms ‘process architecture’, ‘business process architecture’ and ‘enterprise process architecture’ are used synonymously. A process architecture includes not just the hierarchical description of process activities, but also the related resources, documentation, performance measures, measurement methods, and governance arrangements. The simple, but indicative, process architecture shown in Figure 3 is an abridged version of an architecture developed for an IT service vendor.

There are also many ways of drawing a process architecture.

Figure 3 shows shared management and support processes at the top and bottom respectively, and core processes in the middle. Core processes are those that have a direct connection with the customer; at the highest level they are the value chains that represent the delivery of the organization’s strategic value proposition. Management processes are those generally concerned with higher level management decision making and planning. Support processes enable the organization. It should be noted that the term “core process” does not imply a comment on importance—the core processes cannot be executed without the management and support processes. Any process in the architecture that does not contribute to the achievement of corporate objectives should be deleted.

In the current context, a process architecture is not what might in other places be called a “business architecture” or “enterprise architecture” where process is often considered a secondary element. The specific meaning here is the documentation of the highest levels of business processes in an organization, i.e. the pathways through which value is exchanged with customers and other stakeholders. The relationships to business architecture and enterprise architecture are discussed later (Other architectures, page 21).

A well-formed process architecture is a powerful management and decision making tool and can be used to:

- visualize the organization’s set of business processes

- understand how the organization’s strategic intent is executed

- communicate business process information

- concentrate organizational focus on value delivery

- understand the business process interdependencies

- prioritize process analysis and improvement activity

- coordinate process improvement project portfolio management

- provide a repository of business process information.

A process architecture is the primary artifact of process management and improvement. An organization without a process architecture cannot have a coherent view of process management. If there is no documented and agreed understanding of the relationships and interdependencies between key business processes, then there can be no certainty of doing effective process improvement. Cross-functional business processes are the only way any organization can deliver value (products or services) to customers, and other stakeholders outside the organization. This gives the process architecture primacy since it discovers, defines, and documents the value pathways. More than just a picture or a model, the process architecture is a daily aid to strategic and operational management in an organization focused on continuous improvement and delivery of service excellence.

Some examples of process architecture

A process architecture is a simple, but not simplistic, view of how the organization creates, accumulates, and delivers value. It is a practical and pragmatic management tool. Two case studies are used below to illustrate the design and use of process architectures.

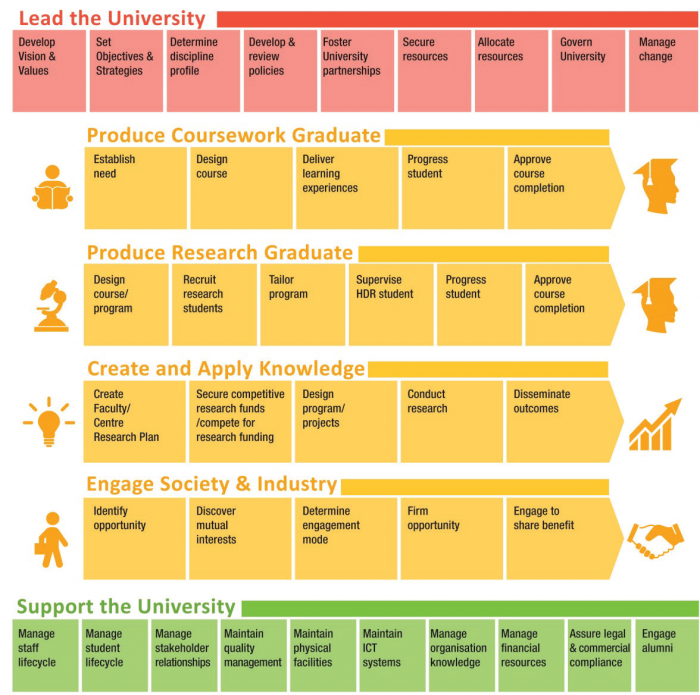

Figure 4 shows the top two levels of business process for a university. Many readers will have suggestions about how it could have been done differently, but this design was thought to be a very good reflection of the university operation by some 100 university staff who participated in a series of development workshops.

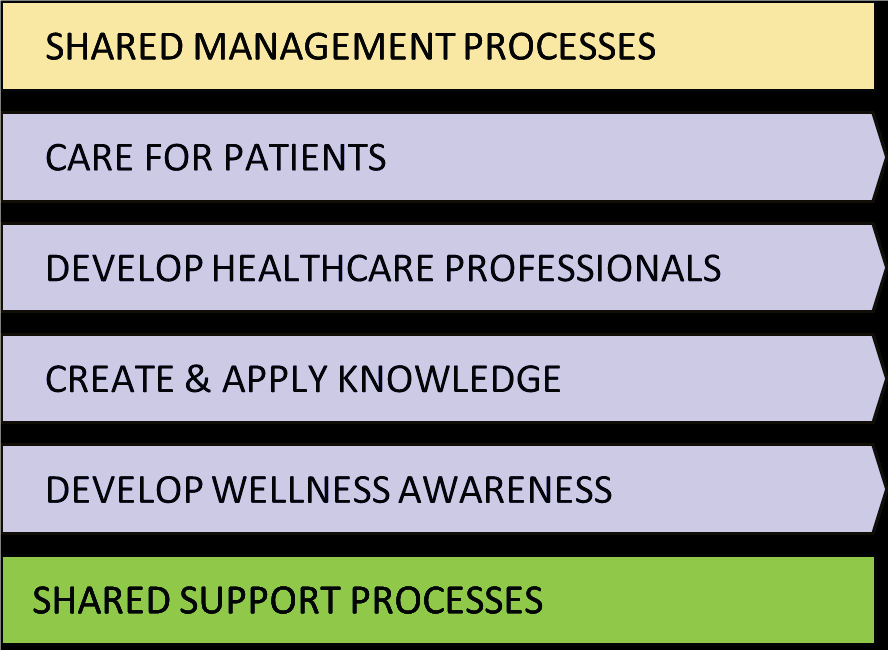

Figure 5 shows another example, this time for a teaching hospital.

Both of these examples of the highest levels of a process architecture hierarchy represent everything that the organizations do. The university creates graduates, conducts research and contributes to society. The hospital cares for patients, develops healthcare professionals, carries out research, and reaches out to improve community health. In both cases there are many other management and supporting processes that make those core activities possible.

A process architecture is a hierarchy of business processes. The examples above show just two levels for the university and one for the hospital. When first developed, two or three levels of the architecture is usually sufficient. Over time, many more levels are defined and detailed as required to address specific organizational performance issues. Every process can be decomposed into sub-processes, so there is no theoretical depth limit. However, in practice, it is necessary to go only as deep as is needed to address a particular issue. It makes no sense to say “we will identify all of our processes”—there needs to be a good strategic or operational reason to make such an investment.

Using a process architecture

A well-formed process architecture is a powerful management and decision making tool that can be used in many ways, some of which are outlined below.

Focus on value

Visualize the organization’s processes. If processes are to be managed and improved they must be defined, collected, and collated – that’s a process architecture.

Concentrate organizational focus on value delivery. Developing and maintaining a process architecture constantly focuses an organization on value delivery via business processes.

Expose ‘value pathways’. Value is created, accumulated, and delivered across the organization chart. A process view means this critical aspect is proactively managed.

Gain agreement about process deliverables. To agree a process architecture it is necessary to get agreement about the processes, what value they should deliver, and to whom.

Enhance communication

Provoke powerful conversations. Asking “who are our customers and what value do they get from us?” causes powerful and valuable conversations.

Engage all stakeholders (internal and external). To develop a process architecture, a list of stakeholders and an assessment of the value delivered to them are prerequisites.

Provide repository of process information. A process architecture model provides a single place where all process information can be stored or linked; a portal to the process view.

Facilitate process performance management

Communicate process performance information. To focus everyone on value delivery, process performance needs to be defined, measured, reported, and discussed.

Define interfaces to external parties. Processes traverse organization boundaries to interact with external processes. Such interfaces can be defined in a process architecture.

Understand process interdependencies. No process exists in isolation; change one process and others will also change. A process architecture uncovers these interdependencies.

Prioritize process analysis and improvement activity. Every organization has many processes. Where is the best return-on-effort in analysis and improvement?

Coordinate process project portfolio management. The output of one process is an input to another. Uncoordinated change might just create a new problem or move the old one.

Developing and maintaining a process architecture is not about abstraction (or abstract art!), it is about providing practical, proven, and effective support for the achievement of organizational performance goals through evidence-based, coordinated improvement in the ecosystem of business processes.

Strategy execution – the process pathway

Cross-functional business processes are the only way any organization can deliver value outside of the organization. It follows, therefore, that an organization also executes its strategic intent via its processes; its value proposition is delivered to customers via its business processes. This important point supports the ‘primacy of process’ and demands close attention to effective and sustained process management and improvement.

For many organizations, and their teams and people, there is a significant disconnect between strategy and process, between the mission-vision-values statements, or their equivalents, and the business process pathways that operationalize the strategy. Strategy development is inherently a top-down activity. Business process management and improvement is often conducted in a bottom-up or middle-out fashion. With the strategic view ‘coming down’ and the process view ‘going up’ there is a real chance that both fade to gray before they meet. In the resulting ‘gray zone’ the strategy loses its clarity and purpose and process activity fails to coalesce into holistic management practice. Too many organizations end up with two seemingly unrelated conceptual views of the enterprise: the strategy, perhaps with strategy themes and a strategy map, and the process view shaped as value chains, process hierarchies and detailed models.

A coherent view of the inter-relationships between strategy and process makes it more likely that the strategy will be executed and the processes will be effectively managed. This requires, not just a good strategy, but also a well-developed process architecture.

Developing Strategy

The complexity of developing statements of strategic intent (mission, vision, values etc.) should not be downplayed. Where there is disagreement amongst the stakeholders the exercise is even more difficult. Resolving the fundamental questions about ‘why are we here’ is always challenging and time consuming, and ultimately, enlightening.

Whatever detailed approach is used, developing strategy can be seen as essentially about answering three, quite complex, questions:

- Who are we?

- Who are our customers and other stakeholders?

- What we do for each other?

Who are we? What do we want to achieve? What do we have to offer? What are our strengths and weaknesses? How are we different to others?

Who are our customers and other stakeholders? Who will want our offerings? Why us? What is our target market? Apart from customers, who else must be satisfied?

What do we do for each other? What is our value proposition? What will customers and other stakeholders be prepared to exchange for that value?

The strategy development exercise results in artifacts such a strategy map and strategy themes or their equivalents, along with strategic objectives.

THE WHYTE & BRITE LAUNDRY

Whyte & Brite has operated successfully for six years and now employs 73 staff. They first started with just the two of them working out of Mike Whyte’s garage. Now they have a large purpose-built site with an investment of nearly a million dollars in plant and equipment and two types of customers: commercial and personal.

Personal customers are individuals who bring clothes to Whyte & Brite for cleaning and, where required, ironing. They also return to collect their clothes. Mike and his partner, Barbara Brite, know that the key to the personal customer business is friendly, personal service.

Commercial customers, e.g. hotels, have large amounts of regular washing. Whyte & Brite tender for this work and contracts detail charges and service levels requiring on-time delivery of high quality service. There is little personal contact and performance is measured on contractual terms.

Mike and Barbara have also been considering a new service where they purchase the sheets, towels and other items and effectively lease them to the commercial customers.

Whyte & Brite has completed a strategy development project. Mission and vision statements are available, along with strategic objectives and a strategy. This gives a coherent view of who they are, who their customers are, why they choose them, and what they offer each other.

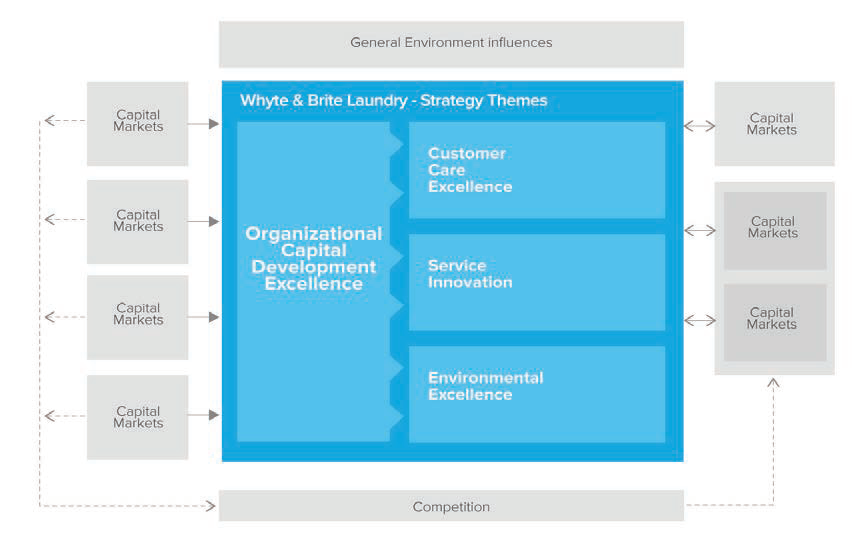

There are four strategy themes that define the strategic intent:

• customer care excellence

• service innovation

• environmental excellence

• organizational capital development excellence.

Figure 6 illustrates the strategy themes in a BPTrends Associates organization diagram3 (derived from the Rummler and Brache Relationship Map4), which can be used in many ways and becomes a diagrammatic repository for strategy and process information. In this diagram, the largest colored box is the Whyte & Brite organization and everything outside the box is the external environment in which it operates.

Managing processes

Managing processes

The Whyte & Brite process architecture is as shown in Figure 7. In this diagram two particular support processes are highlighted because of their direct relevance to the strategy themes.

The multi-layer process architecture shows all of the processes by which Whyte & Brite delivers value to all of its customers and other stakeholders. It was developed in a series of workshops based on the value propositions defined in the strategy. The process architecture is the way in which Whyte & Brite operationalizes its strategic intent.

Strategy + process

Figure 8 closes the loop and shows how the key processes from the process architecture operationalize the strategy. The link between high level processes (and their many sub-processes) and the key elements of the organization’s strategic intent facilitates a clear view of how the strategy is executed. Particular initiatives related to the strategy can now be seen as changes to the related processes. Measurement and management of process performance tracks the execution of the strategy.

The Whyte & Brite Laundry case is a simple one; real life is more complicated. However, the essential connection between strategy and process is clear and provides a compelling reason for an organization to develop, document, and maintain its process architecture.

Other architectures

There are many “architecture” types often used in the planning and management. As well as business architectures and enterprise architectures, there are architectures that address IT, information, capabilities, services, systems, rules, applications, organizations, and people. While there are some quasi standards, there is no definitive, accepted standard. The common, and often overlapping, definitions of business or enterprise architecture do include a business process component, but not as the central element.

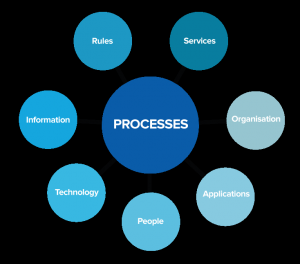

This paper does not seek to either explain or reconcile the many views of business/enterprise architecture (Further information can be found using search terms such as BIZBOK, FEAF, Zachman, and TOGAF), but it does have a particular architectural stance. The concept that underpins this paper, indeed this series of papers, is the ‘primacy of process’. This says that because an organization can only deliver value to customers and other stakeholders via its processes, and therefore it also executes its strategy via those processes, the processes need to be the focal point of any architecture. Figure 9 shows a generic view of a process-centric enterprise architecture. All of the commonly used architectural perspectives are still valid, but the process context is fundamental. Emphasizing the process-centric nature of the framework, each perspective has a direct relationship to the process context. This also emphasizes that the relationship of each perspective to all other perspectives is defined by the architecture of business processes. In order to understand, measure, and improve an organization, this picture stresses that one must first understand how value is created and delivered to the customer in relation to the complementary perspectives.

This paper does not seek to either explain or reconcile the many views of business/enterprise architecture (Further information can be found using search terms such as BIZBOK, FEAF, Zachman, and TOGAF), but it does have a particular architectural stance. The concept that underpins this paper, indeed this series of papers, is the ‘primacy of process’. This says that because an organization can only deliver value to customers and other stakeholders via its processes, and therefore it also executes its strategy via those processes, the processes need to be the focal point of any architecture. Figure 9 shows a generic view of a process-centric enterprise architecture. All of the commonly used architectural perspectives are still valid, but the process context is fundamental. Emphasizing the process-centric nature of the framework, each perspective has a direct relationship to the process context. This also emphasizes that the relationship of each perspective to all other perspectives is defined by the architecture of business processes. In order to understand, measure, and improve an organization, this picture stresses that one must first understand how value is created and delivered to the customer in relation to the complementary perspectives.

While other architectural constructs are useful and often vital, particularly to guide information systems, the tendency to define ‘every’ object and show the relationships to ‘every other’ object via abstract diagrams, may be of limited benefit to managers.

Accepting the ‘primacy of process’ principle and starting with the process architecture as described in this paper, allows an organization to focus on the purpose and performance of the value pathways. Other architectural elements can be added when they are be shown to add value, when they are an aid to management and not a further complication.

Creating a process architecture

Creating a process architecture is not a trivial exercise, and since it will always be subject to change and the exploration of greater detail, it is a never-ending job. Nevertheless, a useful, working process architecture can be developed reasonably quickly and the immediate value of doing so can be remarkable.

Quite apart from creating a solid basis for effective, ongoing process management, discovery of the process architecture focuses the organization wonderfully on really understanding how it executes its strategic intent.

It is not the intention here to describe in detail how a process architecture is developed. In any case, the development detail is likely to vary significantly between different organizations. However, an overview of the generic approach will be helpful in better understanding the nature, purpose and use of such artifacts.

Broadly, there are six steps in the discovery and documentation of a process architecture:

- Identify the organization in focus

- Understand the organization’s strategic intent

- Discover the customer value proposition(s)

- Name the value chain(s)

- Decompose the value chain(s) to level 1 processes

- Decompose the level 1 processes to level 2 processes

Confirming the boundaries of the organization in question is a necessary first step. Is it a whole organization or part of a group? Are there geographic or other boundaries? Confirmation and review of the vision and mission, or other strategy descriptors, is a necessary precursor to understanding the customer value proposition(s). What value is intended to be delivered to which customers? Who else needs to be satisfied? Based on the value propositions, what are the highest level processes that operationalize the strategy? Naming processes at any level using the verb-noun format, e.g. Produce graduate or Create & apply knowledge, is recommended. From the top of the architecture, processes can be decomposed to as many lower levels as are required—a total of two levels is the recommended minimum for initial architecture design.

Having documented a process architecture, the obvious next question is how should the performance of the processes be measured and managed. They are topics for other papers in this series, but suffice to say here that the process architecture does need to be maintained, and that this needs to be done in a controlled and coordinated way. This is at the heart of process-based management.

Owning the architecture

A process architecture has little purpose unless it is actively used in organization management. Process architectures are created to identify the otherwise undocumented and only randomly managed pathways by which value is created, accumulated, and delivered. If the architecture is not in common use then it is just artwork, and probably bad artwork at that! Process architectures must be owned by the organization, by its people, and by their teams.

To maximize the chances of the process architecture being owned by ‘the business’, the process architecture:

a) must be credible and allow people to see where they make their personal contribution,

b) must be current so it does not come to be seen as an unreliable description of the organization

c) must be communicated so everyone has access to it and plenty of opportunity to challenge and learn its contents, and

d) must be used, and seen to be used, so it is not perceived as some sort of once-a-year poster.

For the many positive effects of having a process architecture to be realized, stakeholders must understand it and believe in it. A process architecture must become a useful management tool, and this requires a sustained effort of communication and explanation.

The architecture and related documentation must be made available in whatever formats will work best for each stakeholder group. Plenty of opportunities must be provided for people to discuss, challenge, and come to understand the architecture and its role in management.

It must also be shown to be at the heart of management decision making via consistent performance reporting against the architecture and demonstrations of its use in enabling process improvement.

Creating a process architecture, and its related artifacts and diagrams, is not just about making ‘posters’, it is about reimagining the organization. For that to happen, with the process architecture as the centerpiece, requires a deliberate and sustained plan to achieve high levels of ownership of the architecture throughout the organization.

The power of process architecture

The case for developing, maintaining, and using a process architecture, can be summarized as providing the organization with the opportunity to:

- define with precision how it creates, accumulates, and delivers value (products and services) to its customers and other stakeholders

- understand how it actually executes its strategic intent

- document the customer experience as a recipient of value delivery via the defined processes

- show all staff, and suppliers and partners, how they contribute to the creation, accumulation, and delivery of customer value

- concentrate everyone on the key task of efficiently and effectively delivering value to customers and other stakeholders

- understand the business process interdependencies and optimize performance

- measure and manage those elements of performance that really matter, i.e. efficient and effective value delivery

- make informed decisions about where and when to invest in process improvement

- coordinate process improvement activity to optimize performance outcomes.

Having a well-developed and maintained process architecture enables an organization to make an important breakthrough in performance management. Cross-functional business processes are the only way any organization can create, accumulate, and deliver value to customers and other external stakeholders. Therefore, strategic intent is also executed via business processes. In conjunction with the rest of the 7Enablers, a process architecture forces the organization to focus on its value delivery purpose, pathways, and performance. A process architecture is a vital strategic and operational management tool. Organizations seeking to do effective process-based management must have a process architecture; without such an architecture there can be no certainty of aggregated process improvement.

The Ideas in Practice

There are many things that might be done in response to the issues discussed in this paper. Below are some practical steps to get started on the creation, verification, maintenance, and active use of a process architecture. Combining these steps with others from the complete 7Enablers set will initiate effective and sustained process-based management. In addressing the 7Enablers, the first step must be to discover, document, and agree the process architecture as this provides a framework for further activity in the measurement, governance, change, mindset, capability, and support enablers.

Clarify strategy

Clarify the organization strategy making sure there is a shared understanding

What is the strategic intent of the organization in focus? Is there a shared understanding of the vision, mission, and values or other strategy artifacts? If not, facilitate the discussions required to gain such agreement. Identify the strategy themes and capture them in an organization diagram.

Confirm value propositions

Define the value (products/services) promised by the organization

Drawing on the strategy statements, define the customers and the organization’s value proposition(s) for them. Are there additional stakeholders who have needs that the organization must satisfy? What does the organization promise to deliver, and what does it expect in return?

Create the architecture

Document the architecture showing the process pathway from strategy to operations

Define the highest level processes to reflect the value propositions, ensuring the core process descriptions cover all of the strategic aspirations. Add the shared management and support processes. Decompose those processes down another level or two. Confirm that the process architecture properly reflects the strategy.

Hang it on the wall

Don’t hide it, let everyone see and comment on the draft process architecture

Socialize the draft process architecture on internal websites or notice boards. ‘Hang it on the wall’ and see what people say. A process architecture cannot be successfully created by just a few people closed away in a meeting room. It will be a community resource and needs to be developed and owned by the community. Getting widespread buy-in is vital.

Define the terms

Create and maintain a glossary of terms and insist on accurate, consistent usage

Everyone needs to talk the same language, to use the same vocabulary, so it is important to define all of the terms that will arise in conversations about the process architecture, both in terms of architecture jargon and the internal terms of the organization. This will greatly reduce the risk of time-consuming and distracting confusion.

Confirm and continue

Modify the architecture reflecting comments as appropriate and engage the other enablers

The process architecture is never complete and will always be changing. Finalize and publish the current working version and mechanisms for controlled change. Continue the discussion about process-based management. Move on to apply the remaining enablers, especially measurement, governance, and change.