Enabler 2: Process Measurement

The 7 Enablers of BPM describe how process-based management reimagines the theory and practice of management. The second of these enablers, process measurement, is discussed in this paper.

A case for systematic measurement of process performance is simply made. It is not possible for any organization to create and deliver value to customers and other external stakeholders except via its cross-functional business processes. This is not just interesting; it is not optional. Products and services are delivered via collaboration across the organization, i.e. by cross-functional business processes. It is, therefore, vitally important that such processes be actively managed and continuously improved.

If processes are to be managed and improved, they must be measured.

Important insights are provided in this paper regarding the development and use of a coherent set of process performance measures. The theoretical requirement is proven, and then the ProMeasure methodology demonstrates practical application along with guidance to avoid common failure modes.

About this Paper

If there is no process performance measurement, there can’t be effective process management—and it will not be possible to know if processes are being improved.

Whether working at the individual process level or across an enterprise, too many BPM initiatives do not deliver on promises made—or, even if the promises are delivered, there is often no solid evidence and, in a skeptical, busy world, the work is dismissed. Staff are asked to be involved in process improvement. They are encouraged to innovate. Six months later, the post-it notes have fallen off the wall and the memories have faded. If strategic, operational and tactical decisions are not being made based on the measured performance of business processes, why would process management and improvement be taken seriously?

It doesn’t have to be like that. The discovery and use of effective process performance measures can be achieved. This paper describes an approach for the consistent definition of the most appropriate measures for the performance of a process and concludes with a discussion of barriers to process performance measurement and related countermeasures.

BPM initiatives that do not incorporate process measurement will fail. Process measurement is not always easy, but it is always possible.

This paper describes the purpose, approach, and use of process measurement in reimagining the management of contemporary organizations.

What you can expect to get from the paper

This paper will provide new insights into the measurement of business process performance and how this is critical to the process-centric view of management. The paper draws on both theoretical concepts, the Leonardo ProMeasure methodology, and practical case studies to illustrate a comprehensive and effective approach to organization performance management. Having considered the content of this paper, the reader will be able to:

- understand the purpose and use of a process measurement

- see the relationship between organization and process performance

- prepare for the challenges of creating a process measurement system

- improve the management of organizational performance

- focus on what really matters—the creation, accumulation, and delivery of value to customers and other stakeholders.

Process Measurement

Why Measure?

Why measure process performance? Because, without measurement, all process analysis and management efforts are likely to prove a waste of time; there is no control over the things that really matter, and organizational decision-making can only be suboptimal.

The only reason for doing process analysis, improvement, and management is to improve organization performance in meaningful ways. No organization has a problem called we don’t have enough process models or process measures. Without measurement, it is not possible to know if there is improvement; it is not clear what is meaningful.

Business processes are the way an organization creates, accumulates, and delivers value to its customers and other stakeholders. On that basis alone, the argument for measuring process performance is easily made. Is value being delivered to customers in a way that impresses them and is sustainable for the organization? The plethora of measures about internal achievement – budget tracking, policy compliance, project completion, people management, etc. – often says little, if anything, explicitly about value delivery. Process performance says it all.

Process performance perspectives

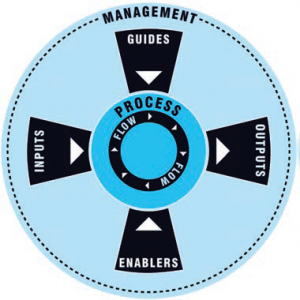

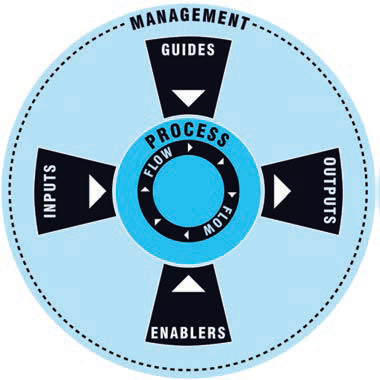

Business processes are collections of cross-functional activities describing the actions required to achieve some outcome. Six operational and performance perspectives of a process are shown in Figure 3. These perspectives provide a balanced view of a process, taking into account both the needs of customers and other external stakeholders, and the equally real needs of internal stakeholders. They are defined as follows.

Inputs: all that is taken into a process and transformed into outputs.

Inputs: all that is taken into a process and transformed into outputs.

Outputs: the results of process execution—the value delivered by the process.

Guides: things that guide or constrain the transformation of inputs into outputs.

Enablers: people, technology, and facilities used to transform inputs into outputs.

Flow: detailed activities within the process that develop and deliver the value.

Management: governance of all aspects of the process; oversight of the other five process performance perspectives.

Process performance management

Process performance measures are the ‘vital signs’ of organizational health, providing a current status assessment, giving clues to possible health issues, and showing progress towards recovery.

A government organization implementing a new service did a lot of planning, created a large number of process models, and had many sessions with a wide range of stakeholders. Green lights everywhere, so the service was launched with appropriate ‘ribbon cutting’. Two days later, all were relieved that the launch had gone well; two weeks later, there was a slowly rising murmur of complaint; two months later, service delivery was in virtual gridlock and the murmur was a cacophony. A month after that, it was finally discovered that a key process in the service delivery was often failing, causing significant rework and introducing inordinately long delays. Further analysis found ways to reduce the delays by 95%. After resolving the backlog, normal service delivery resumed. Customer, and staff, memories of the fiasco will, however, never be erased.

It didn’t need to be like that. Careful analysis of process performance expectations before launch, and appropriate measurement of process performance from launch, would have either avoided the problem completely, or detected it early and allowed resolution before it became a major issue.

A great deal can be gained from effective process-based management, but every organization has the right, indeed the obligation, to demand that those involved continuously demonstrate that the promised benefits have been realized. The process of process management also needs to be constantly improved. For this to be possible, there must be regular assessment of the effectiveness of the changes made. Process practitioners are not in the business of just making recommendations; their purpose is to make positive change—and to prove that they have done so.

Measuring business process performance delivers many benefits:

- factual evidence of customer-service levels

- better understanding of cross-functional performance

- enhanced alignment of operations with strategy

- evidence-based determination of process improvement priorities

- detection of performance trends

- better understanding of the capability range of a process

- uncovering actual and latent problems

- changing behavior based on factual feedback

- improved control over the risks that really matter.

BPM initiatives that do not incorporate process measurement will fail. Process measurement is not always easy, but it is always possible.

Measurement-friendly culture

One of the most significant roadblocks to robust process performance governance—and subsequent process improvement and management—is the absence of a measurement-friendly organizational culture. In an organization where measurement is a precursor to the allocation of blame, the instinct is to measure as little as possible and to conceal the measures that are unavoidable. Where performance measures are collected to facilitate disparagement, enthusiasm for testing and reporting performance cannot be expected.

During a process-improvement project, a strange conversation happened with a senior manager. The project team was investigating a process with a customer satisfaction problem, and had developed three change ideas that would significantly increase customer satisfaction at quite low cost. Quite rightly, the team was pleased with its work. However, the senior manager pushed back and found reasons why the changes should not be made. This went on for several days, with the team dispatching each new objection as it came up. Finally, the manager took the project leader aside and explained that his real concern was that if customer satisfaction increased from 83% to 95%, he would get sacked. He was prepared to accept a new target of 85% and that, over time (a year or two), it might be “safe” to achieve the 95% mark. He was serious. This was a culture of continuous dissembling, not continuous improvement.

Most people will readily agree that continuous improvement is a noble aspiration and a practical objective. The other side of that same coin, however, is to be continuously finding aspects of the organization that are not performing as well as they might. This ‘negative’ perspective is not always as welcome. Explaining to a manager that there are ways to cost-effectively achieve significant improvement in the performance of one of her processes may not be received as the good news it was thought to be. The manager, and the organization, might see that as a past failure rather than an ongoing success.

To some extent, this happens in all organizations. When was the last time that finding a new performance problem triggered a celebration in any organization?

Measurement phobia, caused by an organization’s predisposition to use performance data to censure rather than improve, is the enemy of process improvement and management. The personal, team, and organizational culture must be such that all stakeholders are always looking for, and openly finding, things that need to be improved.

A measurement-friendly culture is a prerequisite for the success of process-based management. Such cultural change needs to be actively nurtured in parallel with the process performance measures discovery ideas outlined in this paper.

Leonardo ProMeasure

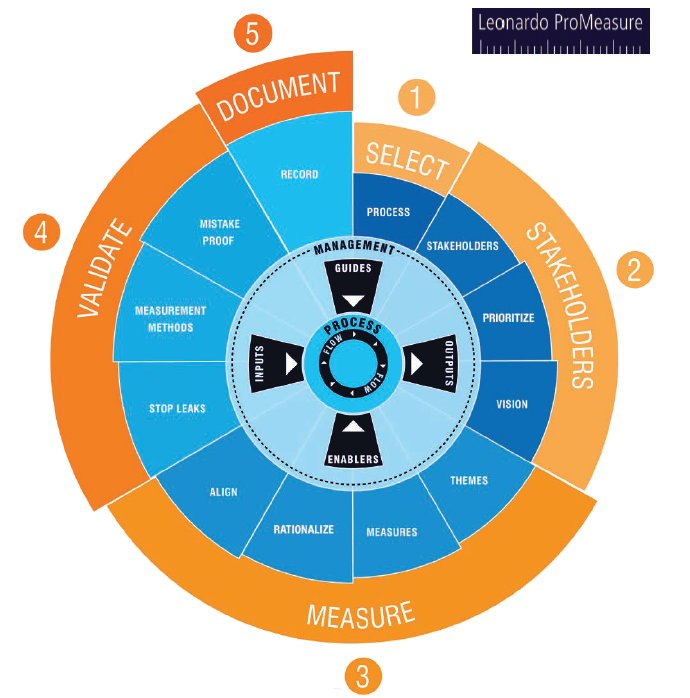

The Leonardo ProMeasure® methodology is shown in the schematic in Figure 4. It provides a consistent and coherent series of 12 steps in 5 phases: from process identification, through to a complete description of the important process performance measures, and their measurement methods, that meet the requirements of the key stakeholders.

Assigning correct performance measures to a process must not be a casual best guess; it should be the result of a systematic, efficient, continuously measured and improved analysis process.

The following sections describe the process performance measurement discovery approach using Figure 4 as a guide. These descriptions do not cover all of the details of the methodology elements, but seek to give an overview of the approach highlighting some of the important steps and tools.

Phase 1, Select: Which process?

It may seem trivial to say that the first step is to identify and select the process. Surely it must be clear which process is to be analyzed? Sometimes it’s not that easy. In any case, it is important to be sure that everyone involved has a shared understanding of the process in question and what the process is generally expected to accomplish.

It is necessary to identify the process and its purpose. These steps need not take long, especially for a process that is already well understood. Neglecting to assure this firm foundation, however, will make it impossible to determine the best set of performance measures. If the organization has a process architecture, then the process in question may have already been named and documented to some extent.

To facilitate development of a shared understanding of the process in question, it is useful to determine and document four of the six process perspectives as shown in Figure 5: inputs, outputs, guides, and enablers. This gives a sound understanding of how the process starts and finishes, to whom or what it delivers value, which systems, facilities, and people are involved, and any policies or regulations that need to be accommodated.

To facilitate development of a shared understanding of the process in question, it is useful to determine and document four of the six process perspectives as shown in Figure 5: inputs, outputs, guides, and enablers. This gives a sound understanding of how the process starts and finishes, to whom or what it delivers value, which systems, facilities, and people are involved, and any policies or regulations that need to be accommodated.

Phase 2, Stakeholders: Who cares?

Stakeholders are fundamental to process measurement and improvement. It is they who define what good performance is, and whether it is being delivered. Processes ‘perform’ for stakeholders—the value delivered by a process is delivered to stakeholders—so their performance aspirations must be the starting point.

It must be clearly understood who the process stakeholders are, and what they want from the process. This is not just a simple, vague list of stakeholder types, but a detailed analysis of stakeholders and their relationships to the process. Many of these will also be deeply involved in the definition of process performance measures.

Stakeholders can cover a wide range including not just the obvious direct customers, but also supplies, regulators, supply chain partners, government agencies, and any other person or organization with an interest in the performance of the process.

Not all stakeholders are equal. It is often difficult to meet the performance aspirations of each stakeholder; there may even be diametrically opposed requirements. Some stakeholders are more engaged with the process than others; some have more power and influence over the design and operation of the process.

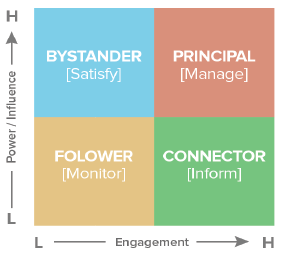

Stakeholder Priority Matrix

Figure 6 shows four categories of stakeholder, arranged to show their relative engagement and influence. “Engagement” means the extent to which the stakeholder has personal or corporate involvement, directly or indirectly, in the execution of the process. A highly engaged stakeholder might be a key tactical resource in executing the process, or it might be that the process is of particular operational or strategic interest. High levels of power and influence mean the stakeholder is either a key decision maker, or has significant influence on decisions about changes to the process in question. Each of these four categories requires a different approach to stakeholder management.

Figure 6 shows four categories of stakeholder, arranged to show their relative engagement and influence. “Engagement” means the extent to which the stakeholder has personal or corporate involvement, directly or indirectly, in the execution of the process. A highly engaged stakeholder might be a key tactical resource in executing the process, or it might be that the process is of particular operational or strategic interest. High levels of power and influence mean the stakeholder is either a key decision maker, or has significant influence on decisions about changes to the process in question. Each of these four categories requires a different approach to stakeholder management.

PRINCIPAL: These are people with high levels of engagement and significant influence. These key stakeholders should be managed closely as they will have a major say in any change initiatives for the process.

BYSTANDER: Stakeholders with low engagement but high influence levels are not involved with the process in question now, but could easily become so, moving into the Principal category. They must be kept satisfied with information and updates.

FOLLOWER: Low engagement and low power means these stakeholders are unlikely to have any impact on process change decisions and actions. They’ll follow along and need little attention. The only action required is to monitor them in case their status changes.

CONNECTOR: Highly engaged stakeholders with low influence abilities are clearly very involved in the process and will be a good source of information and connection to all involved in process execution. They may also have a negative impact on change initiatives if not kept involved and informed.

All stakeholders above the line, i.e. Principals and Bystanders, will be important in approving any process changes that are proposed. Stakeholders below the line i.e. Followers and Connectors, are likely to be an important source of information about the process in question. In analysing a process to determine its correct measures, it will be useful to involve stakeholders from the two right-hand quadrants, i.e. Principals and Connectors, for their knowledge, as well as those above the line for their influence.

In discussions with the stakeholders, it is useful to take a top-down approach to determining the process performance measures. A discussion about what sort of performance is most important will identify key measurement themes, and an important outcome of such discussions is an early prioritization of what is most important. An organization can’t, and doesn’t want to, measure everything.

Based on a good understanding of stakeholder needs, a vision can be developed for the process performance. If the process is doing what key stakeholders require of it, what is it doing and how would that ideal achievement be best characterized?

Phase 3, Measure: Which measures?

ProMeasure began by creating a shared understanding of the process and agreeing on its purpose and boundaries. Then a deep insight into the process stakeholders and their performance needs was developed. Next, building on that sound foundation, an initial long list of potential measures is made.

Possible process measures can be collected and sorted by key stakeholders against the six perspectives of process performance identified earlier. At this stage, it is useful to capture as many reasonable measures as possible. The list will be rationalized in the next step. For now, it is important to capture every measure that the stakeholders would consider relevant and should, if possible, be satisfied.

An impressive sequence of thought leaders have travelled before us in seeking to understand what is really important about performance measurements—Pareto, Juran, Deming, Ishikawa, and many more. Pareto’s 80/20 ‘rule’ was more generally interpreted by Juran, giving rise to the concept of the “vital few and the trivial many”. Having previously created a long list of candidate measures, it is now necessary to rationalize them, to determine the vital few. This is not just a matter of neatness or simplification for its own sake. The more measures that are ultimately assigned to the process, the more data must be collected and assessed—Goldilocks theory5 applies: not too few, not too many, but just the right number of measures.

The long list of candidate measures can be rationalized by testing them for redundancy, importance, practicality, completeness, clarity, and fitness for purpose. Measures may also change over time; what is appropriate to measure now—perhaps immediately following a change—may not be the best measure in 12 months’ time.

Ultimately the question to ask is whether the process performance analysis and design work has created a viable set of the minimum number of important measures of actual process performance about which there is key stakeholder agreement, and for which there are measurement methods that can cost-effectively gather objective, accurate data against a well-defined target.

No process exists in isolation, and neither does a performance measure. Every process can be decomposed into component processes. It follows that every process is part of another at a higher level, up to the highest process architecture level. Although an organization may not actively do so, all processes at every level can be measured. Therefore, in parallel with the process hierarchy, there is a hierarchy of process measures.

The analysis issue at this point is to determine if there are any important misalignments between process measures at the same or higher levels. The key questions to be addressed include:

- Does the set of process measures align with the next highest process level?

- Are there gaps in the set of process measures compared to the next highest level?

It is a common occurrence to discover that personal performance KPIs are misaligned. A staff member with the objective to improve customer service and reduce cycle time might be in futile conflict with a supervisor whose main goal is to reduce costs.

Phase 4, Validate: Are these the best measures?

Now the list of candidate measures can be given a final test for completeness, practicality, and usefulness.

Stop the leaks

Performance leakage points (PLPs) are places and circumstances in the process where problems are more likely to develop. There is no certainty about this for a particular process in its unique circumstance, but experience shows that any process may have a problem at:

- handover points

- queuing points

- places that create rework

- customer touch points

- points of complexity

- time-critical activities.

Having identified proven or potential PLPs such as these, it is useful to consider whether the candidate process measures would effectively provide an alert to performance issues at those points. Where performance problems might develop, will the measures provide an early warning?

Imagine a commercial laundry where customers bring in clothes for washing or dry cleaning for same-day service. Where could that go wrong? Are there any measures that could act as an early warning of potential problems? The genesis of many problems might be found at the front counter. Should staff just keep taking in more clothes, pleased that “business is great today”? Alternatively, it might be useful to continuously measure capacity, looking to forecast the point at which the same-day service promise cannot be met. The process Clean Clothes has a finite capacity. If the customer is thinking I’ll pick this up at 5:15 and front counter staff are thinking we’ll do our best, that’s probably not going to end well.

Measurement methods

In assigning measures to processes, care must be taken that, for each measure, there is an effective measurement method. It is too easy to create a measure for which the data gathering is very difficult or costly, or perhaps just not practical. Where will the data come from? Does it already exist, or is a new process required to collect, collate, and analyze it? Is the measure quantified enough to allow effective data collection? If it was said that a service was going to be ‘the best in town’, what does that really mean? Perhaps it means that ‘98% of our customers will rate the service at least 8.5 out of 10’. Where will that data come from? How much? How often? At what cost?

For every process whose performance is to be actively measured, there needs to be a practical, reliable, accurate (enough), and cost-effective measurement method for each process performance measure.

Mistake-proof

If a process could be made to be ‘mistake-proof’ it would not need to be measured. If a process cannot fail to meet its performance targets, nothing needs to be measured. Unfortunately, that happy circumstance is not to be found in this world.

However, there are things that can be done to most processes that reduce the likelihood of poor performance. To the extent that a process can be made mistake-proof, even in a small way, the need to measure some aspects of performance is removed. Good performance cannot be measured into a process. Measurement for its own sake is waste, so removing the need for measurement should also be a goal. For example, efforts could be made to develop a better understanding, and ability to measure and forecast, process capacity utilization so as to avoid over-stressing the process. Automated responses might be triggered as a process nears a capacity limit, beyond which, performance problems would be inevitable. Other software or mechanical controls—such as calendar reminders, approval limits, checklists, restock indicators, pop-up information screens—may help reduce the possibility of performance errors.

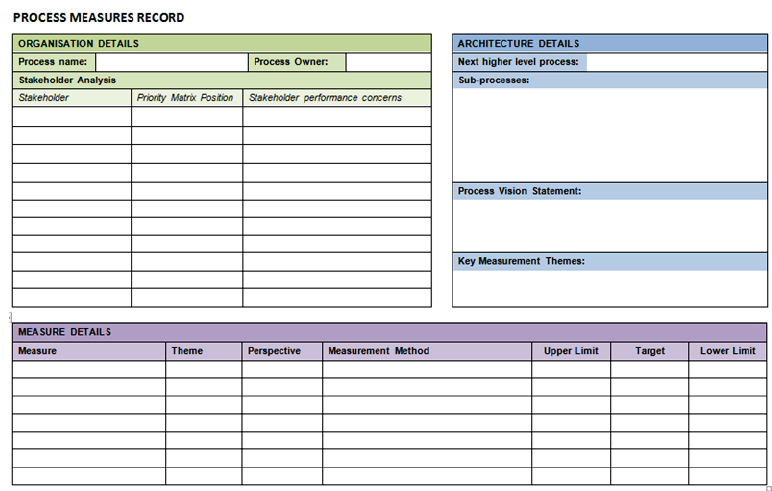

Phase 5, Document : Record the measures

The importance of the final step is often underestimated. There is a need to collect the analysis artifacts to make them available to all who study, manage, and execute the process. This data may be in simple tabular form or part of the repository associated with an appropriate modelling tool. One example of the performance record data that might be collected is shown below, reflecting the steps in the ProMeasure methodology.

Common failure modes

Most organizations do not do effective process performance measurement. Many don’t do it at all. An organization not measuring process performance, is not doing process management, and cannot know if it is doing process improvement.

There are many barriers to effective process measurement. Some are described below along with countermeasures. The approach described in this paper delivers such countermeasures.

Barriers

Countermeasures

Inappropriate measures

- Use a consistent methodology for the definition and management of process measures

- Avoid having too many, or too few, measures

- Control the costs of performance data collection, analysis and publication

- Connect process performance to strategic and operational management

- Avoid a process measurement focus that is too narrow

Disconnection from value creation

- Design process measures to reflect real needs of key shareholders

- Regularly review process measures to ensure they continue to reflect stakeholder needs

- Build process measures into management decision-making

Lack of accountability

- Ensure that nominated roles/people are accountable for responding to performance data (i.e. maintain effective systems of ‘process ownership’)

- Publish regular reports of process performance

Lack of confidence in performance measures

- Ensure that process measures, targets, and measurement methods are well understood

- Clearly define and publish the details of the ‘process of process measurement’

- Regularly test the reliability of data sources

- Continue to consult with key stakeholders

Fear of measurement

- Develop a measurement-friendly culture

- Focus on the performance of the process, not the people

- Give positive acknowledgement to the discovery of problems

- Publish success stories around improvements generated via process performance measurement and response

Achilles’ heel or cornerstone?

Organizational performance improvement means increasing the value exchanged with customers and other stakeholders. Process-based management offers the potential for significant, sustained, and controlled improvement in areas that really matter.

Organizations, and the people who work in them, must embrace the search for improvement that can only result from underperformance uncovered by measurement. Improvement and management of business processes demands that we determine performance targets, collect performance data, and make decisions based on process performance outcomes.

Measurement of process performance is the Achilles’ heel of many initiatives to develop a high-performance, process-centric enterprise. It must be the cornerstone.

To deliver on the promise of BPM, process performance must be measured.

The Ideas in Practice

There are many things that might be done in response to the issues discussed in this paper. Here are some practical steps to begin the development and use of a process performance ‘architecture’.

Combining these steps with the other enablers will initiate effective and sustained process-based management. In addressing the 7Enablers, a critical step is to design effective process performance measures, and measurement methods, so as to give practical substance to the need to manage and improve business processes.

Create the architecture

Document the process architecture to show context for the individual processes

While it is possible to work on a single process in isolation, it is much more effective to be looking at a process in the context of its overall ecosystem. Understanding the context, as well as the content, of a process will result in a better set of performance measures reflecting operational realities.

Engage stakeholders

Identify and engage those who care about the performance of the process

Processes deliver value (products and services) for stakeholders, so ultimately it must be the stakeholders who decide if the process is performing as it should. They need to be, not just identified, but engaged and involved in the analysis of the process, if the optimum performance measures are to be identified.

Document the measures

Find, refine, review, and document the measures and measurement methods

Of course, this is the difficult, time-consuming, and absolutely critical element. Start with a process architecture, at least a high level one, and develop performance measures from the top down. If these processes were working as well as the stakeholders require, what would they be doing and how would that be measured?

Report performance

Don’t hide the process performance results—good, bad, or ugly

An organization that proclaims a commitment to the ‘primacy of process’, and to measuring and improving processes, must report consistently, irrespective of the performance levels. While it might be tempting to do so, reporting only on the good news will not create a measurement-friendly culture or an urgency for change.

Respond

Do something if the reported process performance is not what it should be

Don’t just collect and report, do something with the information. The ultimate purpose of all process analysis is to improve organizational performance in meaningful ways, so the real work starts after the process performance is reported. Which process performance gaps need to be closed now, why those, and what will be the business benefits of doing so?

Create commitment

Do everything possible to create and sustain widespread buy-in to the measures

Implementing a new, and possibly challenging, set of performance measures is not easy. There will be resistance, especially if the performance results are initially below target. Persistence is required and that can only come from a deep understanding of, and commitment to, the need to measure and report process performance.

Leonardo ProMeasure® Methodology Overview

ProMeasure ensures that the most effective process performance measures, with maximum support from stakeholders, are discovered, designed, and documented, thereby allowing practical realization of the benefits of process-based management.

PHASE 1: SELECT

There is just one important step in this first phase. Which process should be analyzed and is there shared understanding about its purpose, scope, and context?

STEP 1 IDENTIFY PROCESS

Identifying and selecting the correct process for measurement may not be as simple as it seems. There are many considerations that need to be evaluated, including: problems, impact, priorities, resources, ROI.

PHASE 2: STAKEHOLDERS

Processes deliver value (products and services) to customers and other stakeholders. It is vital, therefore, to understand who they are and what they expect.

STEP 2 IDENTIFY STAKEHOLDERS

It is important to clearly identify, and appropriately involve, all important stakeholders to ensure their views are known and considered, and any disagreements resolved (or at least understood).

STEP 3 PRIORITIZE STAKEHOLDERS

Not all stakeholders are equal. It is important to know which stakeholders have high levels of authority and influence and which are the most involved in the process.

STEP 4 PROCESS VISION

If the process was working as well as the stakeholders would like it to, what would it be doing and how could that be known—what is the stakeholder vision of good performance?

PHASE 3: MEASURE

In this important phase measures are discovered, rationalized, and aligned to ensure a coherent set reflecting what the process should achieve to satisfy its stakeholders.

STEP 5 DETERMINE THEMES

There are many ways to measure the performance of a process. Before moving to specific measures, what is the general performance requirement of the process?

STEP 6 ASSEMBLE MEASURES

The long list of all of the possible measures across the six perspectives of process performance is formed reflecting current operational details, stakeholder requirements, observation, and reference models.

STEP 7 RATIONALIZE MEASURES

Select the ‘vital few’ measures from the ‘important many’. Remove redundant, unnecessary, and irrelevant measures, leaving a few clear and concise measures.

STEP 8 ASSESS ALIGNMENT

This simple but important step ensures that the selected process measures in sub-processes are not misaligned to higher level processes causing sub-optimization.

PHASE 4: VALIDATE

Continuing to refine the candidate measures, reality checks are applied to test for cost-effective data gathering, pragmatic focus, and redundancy in the measures.

STEP 9 STOP THE LEAKS

There are often parts of a process that are more prone to problems than others, e.g. customer touch points and time critical activities. Measures can be assigned to prevent such process performance ‘leaks’.

STEP 10 DOCUMENT MEASUREMENT METHODS

The measurement method, or the way performance data is collected and collated, has to be credible, cost-effective, and reliable. It is too easy to design measures for which practical collection is not possible.

STEP 11 MISTAKE PROOF

If a process is ‘mistake proof’ there is no need to measure its performance. While such perfection is not a real expectation, steps can be taken to restrict failure points, thus reducing the measurement load.

PHASE 5: DOCUMENT

The last important step in this final phase is to clearly document both the agreed measures and the justification for their selection as the key process measures.

STEP 12 RECORD MEASURE

All of the data created in the previous steps need to be collected, collated, and recorded and made available for all stakeholders and for future analysis and management.