Beyond Alignment: Applying Systems Thinking in Architecting Enterprises

Edited by John Gøtze and Anders Jensen-Waud

ISBN 9781848901162

The book is a comprehensive reader about how enterprises can apply systems thinking in their enterprise architecture practice, for business transformation and for strategic execution. The book’s contributors find that systems thinking is a valuable way of thinking about the viable enterprise and how to architect it.

Introducing Beyond Alignment

John Gøtze and Anders Jensen-Waud

Abstract

This chapter is an introduction to the book. The editors explain why enterprise architects must move beyond having alignment of “business” and “IT” as their focal point. Instead, the editors suggest, enterprise architects should apply Systems Thinking.

Keywords

Enterprise Architecture, Systems Thinking, alignment

The Alignment Debate

There has been a longstanding debate in the literature about what alignment means. Some of the definitions used in peer-reviewed articles specific to an IT-context are the following:

- The degree of fit and integration among business strategy, IT strategy, business infrastructure, and IT infrastructure. Henderson and Venkatraman (1989)

- The degree to which the mission, objectives, and plans contained in the business strategy are shared and supported by the IT strategy. Reich and Benbasat (1996)

- The basic principle is that IT should be managed in a way that mirrors management of the business. Sauer and Yetton (1997)

- Good alignment means that the organization is applying appropriate IT in given situations in a timely way, and that these actions stay congruent with the business strategy, goals, and needs. Luftman and Brier (1999)

- Strategic alignment of IT exists when an organization’s goals and activities and the information systems that support them remain in harmony. McKeen and Smith (2003)

- Alignment is the business and IT working together to reach a common goal. Campbell (2005)

In May 2013, a research library database counts 281.152 peer-reviewed articles about “alignment”, and 21.199 about “business-IT alignment”. Alignment in an IT-context is today generally understood as the ability of the IT department to support the business department’s mission, vision and plans. When aligned, employees in IT act in such a way that their actions stay congruent with the business strategy, goals, and needs.

Since 2010, alignment researchers even have a dedicated journal, the International Journal of IT/Business Alignment and Governance (IJITBAG), which puts emphasis on “how organizations enable both businesses and IT people to execute their responsibilities in support of business/IT alignment and the creation of business value from IT-enabled investments”.

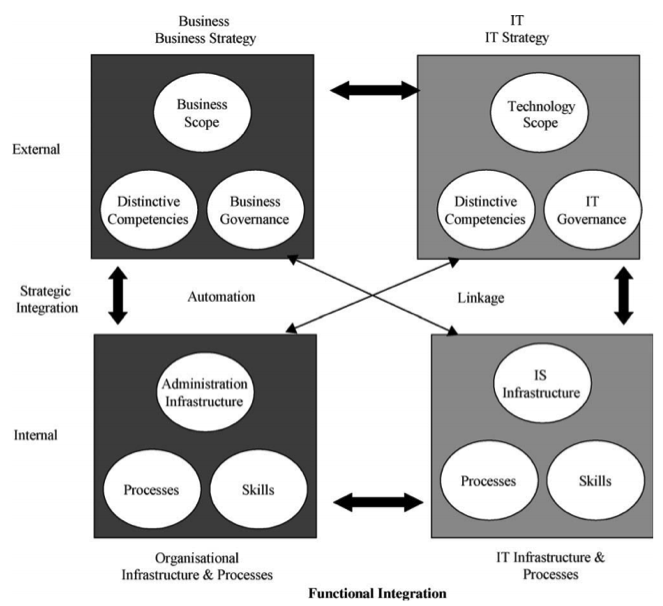

Henderson and Ventrakaman (1989) developed a strategic alignment model to delineate alignment between IT and business. The model features two types of integration: strategic integration and functional integration. Strategic integration is about alignment between strategy and operations, and is the alignment between the external and internal organizational domains. As Figure 1 illustrates, strategic integration exists for the business and IT units. Functional integration involves two types of alignment: One between business and IT strategy, and one between organizational infrastructure and processes and IT infrastructure and processes.

The functional integration on the strategy level is concerned with the integration about the position of the firm for both domains. On the infrastructure level, functional integration is about the relationship between organizational processes, skills and infrastructure and the IT infrastructure, processes, and skills. Also, cross-domain alignment is the relationship between the IT strategy level and the organizational infrastructure and processes level, and the business strategy and the IT infrastructure and processes level. Strategic alignment at an organizational level can only occur when three of the four domains are in alignment. The underlying premise is that change cannot happen in one domain without impacting on at least two of the remaining three domains in some way (Avison et al., 2004). The distributions of domains that are either anchor, pivot, or impacted determine the organization’s alignment perspective. The anchor domain is the strongest domain and will be the initiator of change and provide the majority of requests for IT resources. The pivot domain will ultimately be affected by the change initiated within the anchor domain. The impacted domain is impacted the greatest by the change initiated in the anchor domain. The strategic alignment model provides a more nuanced conceptualization of alignment. The IT-business relationship can take different alignment perspectives. Further, the model proposes that effective strategic IT management process must address both functional and strategic integration (Henderson & Ventrakaman, 1989).

Maas (1999) and Maes et al. (2000) extended the strategic alignment model to a unified framework that incorporates layers into the model to reflect the need for information and communication. The unified framework refines the alignment model to reflect the fact that IT and business strategies are moving closer together as technology evolves and becomes more integrated (Avison et al, 2004). The unified framework deals with the relationship between business, information, communication and technology at three distinct levels: strategy, structure, and operations (Maes et al., 2000). Strategy is constituted by core competencies, governance and scope; structure is constituted by architecture, communication processes and information models; and operations are constituted by processes, modeling and skills.

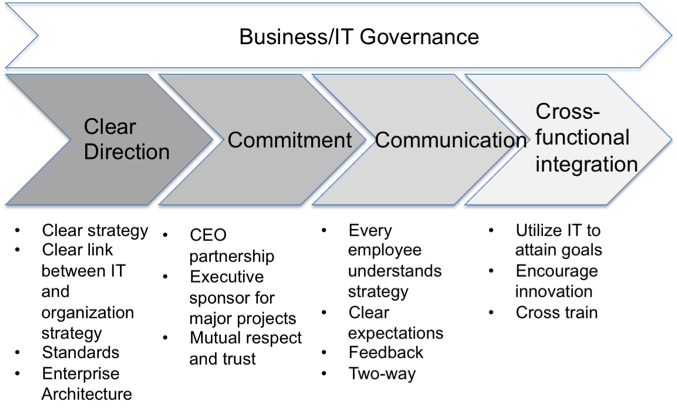

A stream of research has investigated the antecedents of IT-business alignment to improve understanding of the alignment process. Weiss & Anderson (2004) found four common themes they found were repeated in organizations with a good level of IT/business alignment. These themes are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Path to alignment, the Four Cs (Weiss & Anderson, 2004)

Similar thinking can be found in MIT CISRs research. Fonstad and Robertson (2006) argue that in order to get alignment the enterprise needs to have both a top-down organizational view and a bottom-up project view. This is reflected in MIT CISR’s IT Engagement Model:

There are studies showing that when organizations adopt a proven framework for alignment early in the planning process, these organizations save time and resources in the long run (Kearns and Sabherwal, 2007). Based on an empirical study of 63 firms, Tallon & Kraemer (2003) find that there is a significant IT payoff for firms that practice strategic alignment, and other studies have shown that a strategic fit between business and IT strategies positively affect sales growth, profitability, and reputation (Tallon & Pinsonneault, 2011; Thatcher & Pingry, 2007; Watson, 2007). Other research has focused on the challenges and issues organizations are facing when creating alignment. Chan & Reich (2007) summarize some of the challenges with alignment:

| Alignment challenge description | Alignment challenge elaboration |

| Knowledge and awareness | IT executives are not always privy to corporate strategy, and that organizational leaders are not always knowledgeable about IT. Also, managers are not always knowledgeable about key business and industry drivers. |

| Corporate strategy is unknown | Corporate strategy is unknown or, if known, is unclear and/or difficult to adapt. This poses a significant challenge because most models of alignment presuppose an existing business strategy to which an IT organization can align itself. Formal business strategies are often too ambiguous for business managers to adapt. Managers face ambiguity surrounding the differences between espoused strategies, strategies in use, and managerial actions, many of which may be in conflict with one another. |

| Lack of awareness or belief in the importance of alignment | Many business managers are unaware of the importance of IT alignment and/or have little belief that IT can solve important business problems. Even if IT issues are perceived to have a strong effect on the business objectives, there is no clear belief that IT can solve specific problems. Managers are typically more comfortable with their ability to comprehend business positioning choices rather than IT positioning choices (i.e., critical technology to support business strategies). Strategy has typically been viewed as something applied to the output market, while IT has been viewed as an internal response. |

| Lack of industry and business knowledge | IT alignment was hindered by a lack of knowledge about an industry. In particular, it was found that IT alignment was negatively influenced by the following industry factors: when awareness of an industry’s issues was low and when the interaction of different aspects within the corporate strategy was not well known to managers. Therefore, before managers could use IT solutions to help solve their problems, a deeper knowledge of the banking industry itself was required. A multiple case study showed that shared domain knowledge between business and IT executives was the strongest predictor of the social dimension of alignment. |

| Alignment challenges related to locus of control and the status of IT | When managers are confronted with a business challenge, they make decisions based on their locus of understanding and their locus of control (authority to make decisions). These constraints impact alignment. From this perspective, strategic alignment can be seen as an array of bounded choices made in order to resolve strategic ambiguity. Another contributing factor in the attainment of alignment is the status of IT within the business unit or organization. |

| Alignment challenges related to organizational change | The business environment is constantly changing, and thus there may be no such thing as a ‘state’ of alignment. Alignment is thus the time lag between business and IT planning processes. That is, given that the business environment and technology change so quickly, once an IT plan is enacted, there is a high probability that the plan and the technology are already obsolete. |

Table 1: Alignment challenges (Chan & Reich, 2007)

Critics of alignment emphasize that organizations constantly change and therefore alignment will never be fully achieved (Chan & Reich, 2007). In many organizations the IT department is always struggling to keep up with the business department’s demands and changes. Luftman et al. (1999) did an exhaustive study of inhibitors and enablers for creating IT-business alignment in big companies. Respondents were asked to rank factors enabling and factors hindering IT-business alignment. The top five enablers were “Senior executives support IT”, “IT involved in strategy development”, “IT understands business”, “IT/non-IT have close relationship”, and “IT shows strong leadership”. The top five inhibitors were “IT/non-IT lack close relationship”, “IT does not prioritize well”, “IT fails to meet the commitments”, “IT does not understand business”, and “Senior executives do not support IT”.

The Alignment Trap

Alignment enablers and inhibitors are more often than not described at such an abstract level that they apply to most organizations, yet are very difficult to operationalize. Essentially, alignment theory is difficult to apply and utilize in today’s enterprises. As expressed in Doucet et al (2009):

Infosys recently published a survey in which the major finding is that “Alignment of business and IT organization is the #1 objective of enterprise architecture …” That is certainly goodness, but how about assuring that all parts of the business are aligned with each other? How about ensuring all the oars are pulling together?

Alignment is essentially to the ability of the organization to operate as one by working towards a common shared vision supported by a well-orchestrated set of strategies and actions (Doucet et al, 2009). It covers the need for all parts of an organization to be working together, and is an important concept for complex enterprises that are composed of a number of lines of business and business functions with competing priorities and limited resources.

It is not that IT doesn’t matter, but we need to reconsider the way we work with IT:

It is time for a major transformation of IT. It is time for a quantum leap. For years, the way we have run IT, as a CIO, was to command an army of ordertaking specialist workers, an underground army hidden away in the basement of our companies. These reactive armies of craftsmen are a thing of the past. In a Fusion concept, we need a new breed of professionals, with a new blend of capabilities. The challenge becomes how to crack the culture code in IT transformation? (Hinssen, 2011)

This “culture code” is not about IT, but about management:

A thousand facts and no information, such is the case as we sit in this period of incoherency. Incoherency makes enterprises less manageable. As Gary Hamel said in The Future of Management, “Management is out of date. Like the combustion engine, it’s a technology that has largely stopped evolving, and that’s not good.” (Doucet et al 2009)

The whole idea of business-IT alignment is out of date. In fact, we consider it a trap.

This Book

The idea of publishing this book was originally conceived by John as a textbook for an advanced level masters course named Enterprise Strategy, Business and Technology at the IT University of Copenhagen. The course was created to build on top of John’s Enterprise Architecture course, and the course’s design criterion number one was that it should appeal to John’s “elite students”, a group of highly motivated full-time students at the MSc in Business and Information Technology program at the IT University of Copenhagen and the MSc in Business Administration and Computer Science at Copenhagen Business School, including Anders.

Teaching business strategy and technology alignment concepts at an advanced masters course requires much more than repeating the core curriculum of enterprise architecture. Whilst orthodox enterprise architecture frameworks usually provide in-depth tools and methodologies for taming the alignment of business and IT, very few approaches go further in considering and explaining how to avoid the alignment trap altogether. When teaching a course to elite students we asked ourselves the question – what should these aspiring enterprise architects learn? How could one provide a comprehensive theoretical foundation for thinking about any complex organization in a holistic, integrative manner? Systems thinking was the most compelling answer because it provides 1) a vibrant cross-disciplinary community of thinkers and practitioners and 2) an entire history of academic research, tradition, and frameworks.

In essence, systems thinking provides a plethora of generalized models and approaches to analyzing complex systems, be it human, biological, social, or mechanical, and how they respond to changing internal and external conditions (Jensen-Waud et al, 2012). Enterprise architecture is often employed as a tool to understand and manage the many moving parts of large-scale organizational change – and systems thinking therefore provides a viable theoretical basis for conceptualizing and reflecting upon how and why enterprise architecture is best applied in different situations so as to successfully execute organizational changes for better outcomes (Buckl et al 2009, Zadeh 2012).

A peer-reviewed paper recently published by John discusses how the scope and role of the enterprise architect is gradually changing from problem solving to problem finding and from dialectic to dialogic skills (Gøtze, 2013). The former is expressed in the way in which enterprise architecture has gradually transitioned from the “classic” domain of business drivers and IT requirements into dealing with many different domains of the enterprise, e.g. business strategy, operations, capability development, etc. These non-IT areas typically deal with “wicked”, ill-defined problems, which are very hard to solve with traditional engineering methods (Jensen-Waud et al, 2012). Instead, skills such as continuous learning, exploration, collaboration, and enquiry are required. The latter is expressed in the increasing need for cross-departmental, cross-disciplinary collaboration and learning in the modern organization in order to solve complex business issues (Gøtze, 2013). In the light of this changing role, systems thinking again provides a compelling approach for framing and analyzing these challenges – relevant examples include Stafford Beer’s viable systems model (VSM) (Beer, 1972), Peter Checkland’s soft systems methodology (SSM), which focuses on the human content and enquiry of systemic problems (Checkland, 1985), and Karl Weick’s (2001) concepts of organizational sense-making and loosely-coupled systems.

Beyond Alignment

In a turbulent macro environment and volatile global economy where successful change increasingly depends on systemic enquiry and cross-disciplinary collaboration, systems thinking has never been more relevant. With this book we hope to demonstrate how both aspiring and experience enterprise architecture practitioners can go beyond alignment and implement better and more holistic change initiatives by applying systems thinking to existing work processes and practices.

Many of these concepts are discussed in this book. The book, in essence, discusses the many new issues faced by enterprise architects and suggests how systems thinking can be applied to frame, understand, and resolve them.

After this introduction, the book falls in four parts:

- Part I: Enterprise Architecture and Systems Thinking

- Part 2: The Brain and the Heart of the Enterprise

- Part 3: Practicing Systems Thinking

- Part 4: Systems Thinking in the Enterprise

Part 1 has five chapters about how enterprise architecture and systems thinking work together. Part 2 has six chapters about using the Viable Systems Model in enterprise architecture. Part 3 has five chapters about using systems thinking as a practice framework. Part 4 has five chapters that positions systems thinking in the enterprise.

Contributing authors are (in order of appearance):

- Sally Bean

- Tue Westmark Steensen

- Janne J. Korhonen

- Jan Hoogervorst and Jan Dietz

- Leo Laverdure and Alex Conn

- Mesbah Khan

- Patrick Hoverstadt

- Adrian Campbell

- Mikkel Stokbro Holst

- Olusola O. Oduntan and Namkyu Park

- Tom Graves

- James Lapalme and Don deGuerre

- Harold “Bud” Lawson

- James Martin

- Dennis Sherwood

- Rasmus Fischer Frost and Linda Clod Præstholm

- Olov Östberg, Per Johannisson and Per-Arne Persson

- Peter Sjølin

- Ilia Bider, Gene Bellinger and Erik Perjons

- Jack Ring

- John Morecroft

The book hopefully stimulates, perhaps even provokes, the reader. Those who would like to comment can make reviews and comments on the book’s website: BeyondAlignment.com.

About the Editors

Dr John Gøtze has worked with the interplay between strategy, business and technology since the early 1980s. With over 12 years of experience in the enterprise architecture discipline, John is today CEO of EA Fellows where he runs Carnegie Mellon University Enterprise Architecture Certification Program in Europe. John also leads the Professional Master in IT Leadership program at the IT University of Copenhagen, and teaches at Copenhagen Business School. John co-founded the Association of Enterprise Architects and was Chief Editor of the Journal of Enterprise Architecture from 2010-2013. He holds an MSc in systems engineering and a PhD in urban planning, both from the Technical University of Denmark.

Anders Jensen-Waud is a Managing Consultant and consulting architect within the Architecture & Technology Transformation practice of Capgemini Australia. With more than six years of general consulting experience and a background in defense systems engineering, Anders has deep experience as a consulting enterprise architect within government, defense, energy, utilities, oil and gas, and financial services. He has delivered a variety of architecture and business transformation engagements through Scandinavia and Australia. He is furthermore a published author in a number of international peer-reviewed journals and books. Anders holds an MSc in Business Administration and Computer Science and BSc in Business Administration and Computer Science from Copenhagen Business School.

References

Avison, D., J. Jones, P. Powell and D. Wilson (2004) Using and validating the strategic alignment model. Journal of Strategic Information Systems 13, pp. 223–246.

Beer, S. (1972). Brain of the Firm – The Managerial Cybernetics of Organization. Allan Lane and Penguin Press, London, UK.

Buckl, S., Schweda, CM, and Matthes, F. (2009) A Viable System Perspective on Enterprise Architecture Management. In Proceedings of SMC, 1pp. 483-1488.

Campbell, B. (2005). Alignment: Resolving ambiguity within bounded choices, PACIS 2005, Bangkok, Thailand, pp. 1–14.

Chan, Y. E. and B. H. Reich (2007). IT alignment: what have we learned? Journal of Information Technology (2007) 22, pp. 297–315.

Checkland, P. (1985). From Optimizing to Learning: A Development of Systems Thinking for the 1990s. The Journal of the Operational Research Society, 36(9), pp. 757-767.

Doucet, G., Gøtze, J., Saha, P., Bernard, S., 2009, Coherency Management: Architecting the Enterprise for Alignment, Agility, and Assurance, AuthorHouse.

Fonstad, N. and D. Robertson (2006) Transforming a Company, Project by Project: The IT Engagement Model. MIS Quarterly Executive. 5:1. pp. 1-14.

Gøtze, J., 2013, The Changing Role of the Enterprise Architect. Proceedings of the 2013 17th IEEE International Enterprise Distributed Object Computing Conference Workshops (EDOCW 2013), 9-13 September 2013, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

Henderson, J., Venkatramen, N. (1989) Strategic Alignment: A Model for Organisational Transformation, in Kochan, T., Unseem, M. (Eds.), 1992. Transforming Organisations. OUP, New York.

Hinssen, P. (2011) Business/IT Fusion. 2nd Ed.

Jensen-Waud, A.Ø. & J. Gøtze (2012) A Systemic-Discursive Framework for Enterprise Architecture. Journal of Enterprise Architecture, 8 (3) pp 35-44.

Kearns, G. S., & Sabherwal, R. (2007). Strategic Alignment Between Business and Information Technology: A Knowledge-Based View of Behaviors, Outcome, and Consequences. Journal of Management Information Systems, 23(3), 129–162.

Luftman, J., Brier, T. (1999) Achieving and Sustaining Business-IT Alignment. California Management Review, Fall, 1999, Vol.42(1), p.109.

Luftman, J.A., Papp, R. and Brier, T. (1999). Enablers and Inhibitors of Business–IT Alignment, Communications of the Association for Information Systems 1(Article 11), pp. 1–33.

Maes, R., 1999. A Generic Framework for Information Management. Prime Vera Working Paper, Universiteit van Amsterdam

Maes, R., Rijsenbrij, D., Truijens, O., Goedvolk, H., 2000. Redefining Business–IT Alignment Through A Unified Framework. Universiteit Van Amsterdam/Cap Gemini White Paper.

McKeen, J.D. and Smith, H. (2003). Making IT Happen: Critical issues in IT management, Chichester, Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Reich, B. and I. Benbasat (2000). “Factors that influence the social dimension of alignment between business and information technology objectives.” MIS quarterly 24(1): 81-113.

Ross, J.W., Weil, P. & Robertson, D.C., 2006, Enterprise architecture as strategy: Creating a foundation for business execution, Harvard Business School Press.

Sauer and Yetton (1997) (eds.) Steps to the Future: Fresh thinking on the management of IT-based organizational transformation, 1st edn, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, pp. 1–21.

Tallon, P. P., & Kraemer, K. L. (2003). Investigating the relationship between strategic alignment and IT business value: the discovery of a paradox. (N. Shin, Ed.)Business, 12, 1–22.

Tallon, P. P., & Pinsonneault, A. (2011). Competing perspectives on the link between strategic information technology alignment and organizational agility: insights from a mediation model. MIS Quarterly, 35(2), 463–486.

Thatcher, M. E., & Pingry, D. E. (2007). Modeling the IT value paradox. Communications of the ACM, 50(8), 41–45.

Watson, B. P. (2007). Is Strategic Alignment Still a Priority? CIO Insight, (86), 36–39.

Weick, K. E. (2001). Making Sense of the Organization. Blackwell Publishing, Malden, MA.

Weiss, J.W. and D. Anderson (2004) Aligning Technology and Business Strategy: Issues & Frameworks, A Field Study of 15 Companies. Proceedings 37th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences.