There are eight basic elements that must be present and be designed to work together in each agency EA program:

There are eight basic elements that must be present and be designed to work together in each agency EA program:

- Governance

- Principles

- Method

- Tools

- Standards

- Use

- Reporting

- Audit

These elements ensure that agency EA programs are complete and can be effective in developing solutions that support planning and decision-making.

EA Basic Element #1: Governance

The first basic element is “Governance” which identifies the planning, decision-making, and oversight processes and groups that will determine how the EA is developed, verified, versioned, used, and sustained over time with respect to measures of completeness, consistency, coherence, and accuracy from the perspectives of all stakeholders.

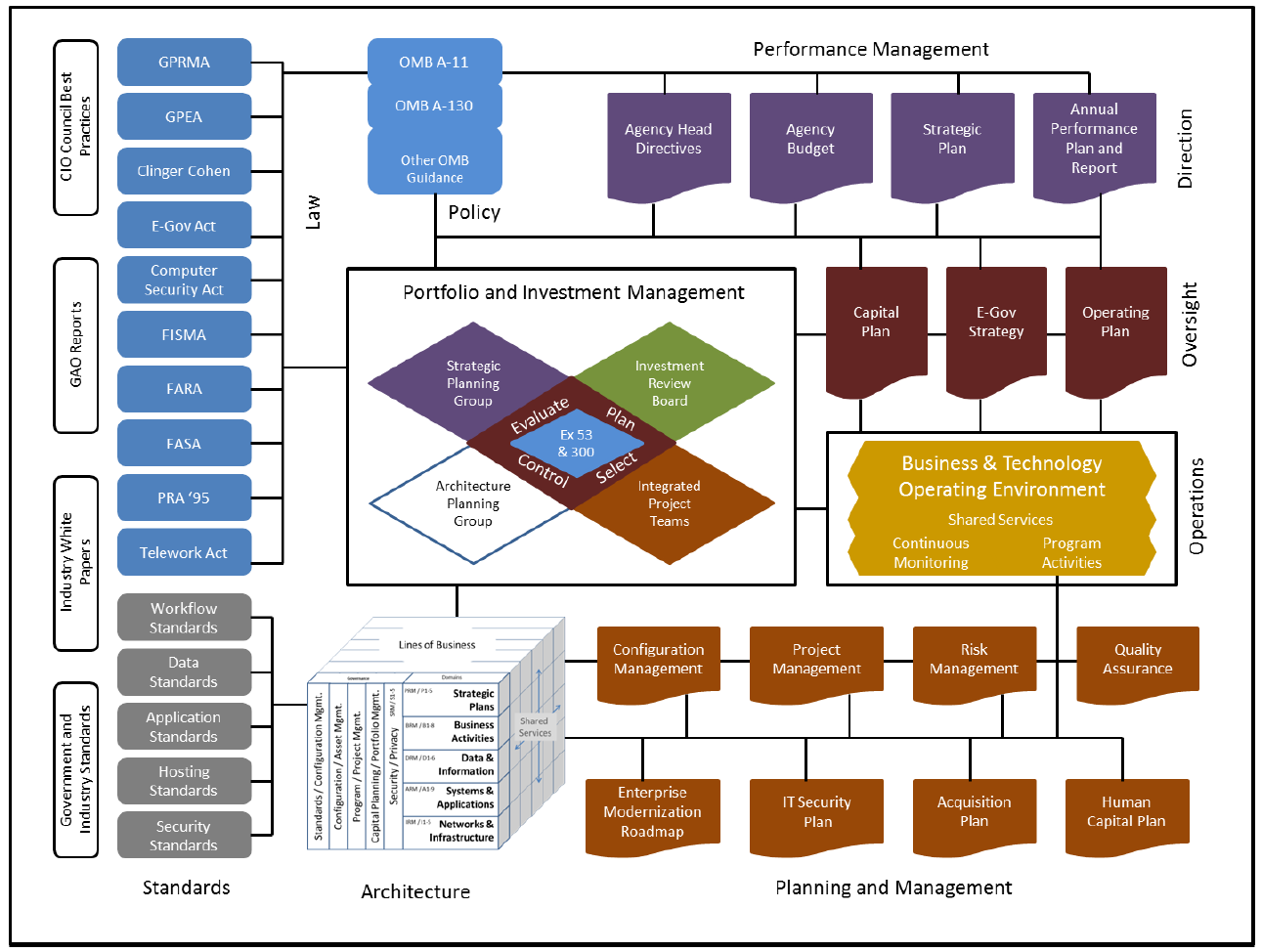

Figure 3 on the next page provides a view of the interrelationships between federal guidance, agency governance processes, and the programs that implement that guidance in an integrated manner. This governance model begins in the upper left quadrant with law and policy; moves to the upper right quadrant where high-level agency directives are represented; moves down to the lower right where operations and planning/management functions are reflected, and finally to the lower left quadrant where architecture and standards are reflected. The model finishes in the center where portfolio and investment management occurs through a number of planning and decision-making bodies. The harmonizing/standards role of EA is depicted as being driven by law and policy and delivering authoritative reference information and design alternatives for the capital planning process in the center.

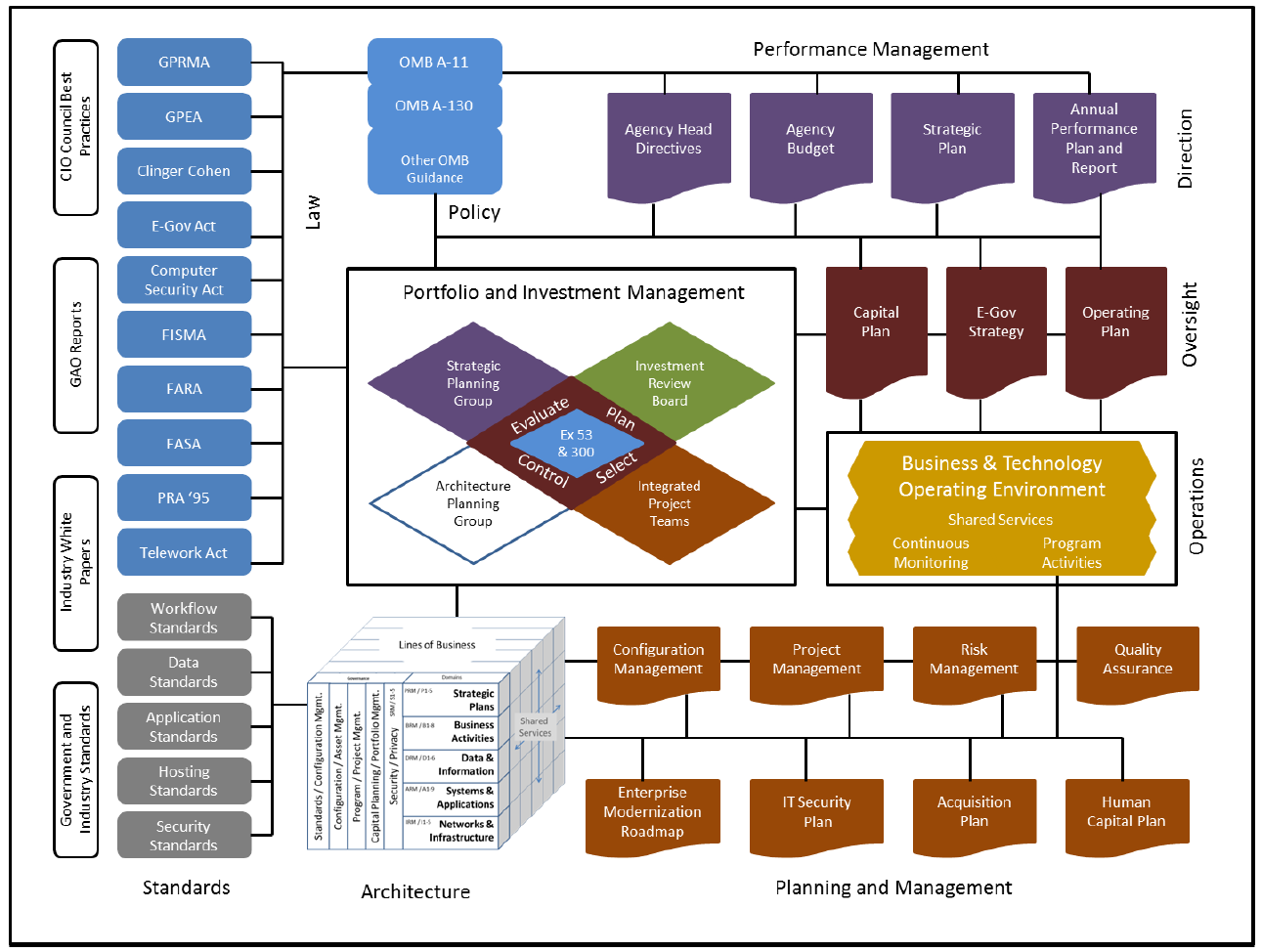

Figure 4 below provides an example of integrated governance structures from a programcentric perspective wherein an Agency’s Program Manager (PM) is the accountable entity and subject matter experts from the business and technology areas are supporting the PM.

Here we are referring to PMs for mission or support programs, not the EA program.

EA Basic Element #2: Principles

General Principles

The following are general principles for the Common Approach to Federal EA and represent the criteria against which potential investment and architectural decisions are weighed.

Future-Ready. EA helps the Federal Government to be successful in completing the many missions that the Nation depends on. Mission requirements continually change, and resources are often limited – EA is the key business and technology best practice that enables Agencies to evolve their capabilities to effectively deliver needed services.

Investment Support. EA supports intra- and inter-agency investment decision-making through an “architect – invest – implement” sequence of activities. Agencies must ensure that investment decisions are based on architectural solutions that result in the achievement of strategic and/or tactical outcomes by employing technology and other resources in an effective manner.

Shared Services. Agencies should select reusable and sharable services and products to obtain mission or support functionality. Increasingly, the Federal Government is becoming a coordinator and consumer as opposed to the producer of products and services. Standardization on common functions and customers will help Federal Agencies implement change in a timely manner.

Interoperability Standards: Federal EA promotes intra- and inter-agency standards for aligning strategic direction with business activities and technology enablement. Agencies should ensure that EA solutions conform to Federal-wide standards whenever possible.

Information Access. EA supports Federal Government transparency and service delivery through solutions that promote citizen, business, agency, and other stakeholder access to Federal information and data, balanced by needs for Government security and individual privacy. EA solutions should support a diversity of public and private access methods for Government public information, including multiple access points, the separation of transactional from analytical data, and data warehousing architecture. Accessibility involves the ease with which users obtain information. Information access and display must be sufficiently adaptable to a wide range of users and access methods, including formats accessible to those with sensory disabilities. Data standardization, including a common vocabulary and data definitions are critical.

Security and Privacy: EA helps to secure Federal information against unauthorized access. The Federal Government must be aware of security breaches and data compromise and the impact of these events. Appropriate security monitoring and planning, including an analysis of risks and contingencies and the implementation of appropriate contingency plans, must be completed to prevent unauthorized access to Federal information. Additionally, EA helps Agencies apply the principles of the Privacy Act of 1974 and incorporate them into architecture designs.

Technology Adoption. EA helps Agencies to select and implement proven market technologies. Systems should be decoupled to allow maximum flexibility. Incorporating new or proven technologies in a timely manner will help Agencies to cope with change.

Design and Analysis Principles

EA is most effectively practiced in a common way at all levels of scope when it is based on principles that guide the actual design and analysis work that goes into architecture projects. The Common Approach to Federal Enterprise Architecture promotes the following design and analysis principles in each of the three primary domains (strategy, business, and technology) that serve as a guide for EA programs and architecture projects:

Strategic Principles:

- Agency IT Strategy and Enterprise Roadmap should be developed in close coordination with broader agency strategic planning efforts to ensure alignment of automated information management processes and investments with overall organization priority

- The structure of Agency IT strategic plans should follow the same fundamental structure as Agency strategic plans and performance documents. Agency IT strategic planning documents should focus on achievement of overall Agency strategic outcomes rather than the optimization of internal CIO processes

- Internal CIO process optimization performance measurement should be managed through lower level planning processes

- The Enterprise Architecture is “the” authoritative reference for planning IT support for optimum business performance

- Agency-wide information sharing and protection policies are specified

- Security and privacy requirement must be identified and addressed

Business Principles:

- Agency business activities exist to meet strategic objectives

- Services should be standardized within and between agencies where possible

- Services should be web-enabled whenever possible

- Security controls must be designed into IT support of every business process

Technology Principles:

- Data and information exchange should be based on open standards

- Privacy considerations must be designed into every data solution

- Use well documented interfaces built on non-proprietary open platforms using standard platform independent data protocols (such as XML)

- Application platforms should be virtualized whenever possible

- Open-source software solutions should be included in alternatives analyses

- Use cloud-based application, platform, and infrastructure hosting designs whenever possible to promote scalability, cost-efficiency, and metering

- Convergence in voice, data, video, and mobile technologies supports infrastructure consolidation, which should be pursued wherever possible

- Host solutions must be compliant with federal policy and standards (e.g., Trusted Internet Connection, IPv6 routing, and PIV authentication)

- Desktop/mobile solutions must be compliant with the latest US Government Configuration Baseline standard

- Security controls must be designed into every technology solution

EA Basic Element #3: Method

In its most successful form, EA is used by organizations to enable consistent planning and decision making, and not simply relegated to use within a single branch of an Information Resource Management Office. In today’s agency operating environment, which demands more efficient government through the reuse of solutions and the use of services, organizations now need an EA community of practice and standard methods that support efforts to leverage other Federal, state, local, tribal, and international experiences and results as a means to most efficiently solve priority needs.

The role of an enterprise architect is to help facilitate and support a common understanding of needs, help formulate recommendations to meet those needs, and facilitate the development of a plan of action that is grounded in an integrated view of not just technology planning, but the full spectrum of planning disciplines to include mission/business planning, capital planning, security planning, infrastructure planning, human capital planning, performance planning, and records planning. Enterprise architects provide facilitation and integration to enable this collaborative planning discipline, and work with specialists and subject matter experts from these planning groups in order to formulate a plan of action that not only meets needs but is also implementable within financial, political, and organizational constraints. In addition, enterprise architects have an important role to play in the investment, implementation, and performance measurement activities and decisions that result from this integrated planning.

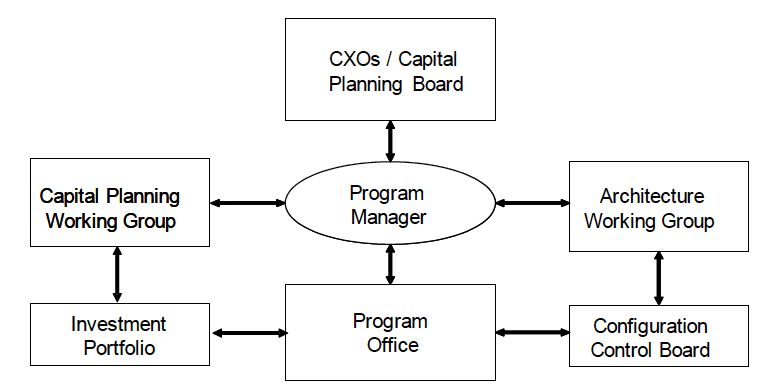

The Collaborative Planning Methodology (CPM), shown in Figure 5, is a simple, repeatable process that consists of integrated, multi-disciplinary analysis that results in recommendations formed in collaboration with leaders, stakeholders, planners, and implementers. The first release of the CPM includes the master steps and detailed guidance for planners to use throughout the planning process. EA is but one planning discipline included in this methodology. Over time the methods and approaches of other planning disciplines will be interwoven into this common methodology to provide a single, collaborative approach for organizations to use. The CPM is intended as a full planning and implementation lifecycle for use at all levels of scope described earlier in the common approach (International, National, Federal, Sector, Agency, Segment, System, and Application).

The CPM consists of two phases: (1) Organize and Plan and (2) Implement and Measure.

Although the phases are shown as sequential, in fact there are frequent and important iterations within and between the phases. In the first phase, the architect serves a key role facilitating the collaboration between leadership and various stakeholders to clearly identify and prioritize needs, researches other organizations facing similar needs, and formulates the integrated set of plans to define the roadmap of changes that will address the stated needs. In the second phase, the architect shifts into a participatory role, supporting other key personnel working to implement and monitor change related activities. As part of the second phase of the methodology, the architect specifically supports investment, procurement, implementation, and performance measurement actions and decisions.

The CPM is stakeholder-centered with a focus on understanding and validating needs from leadership and stakeholder perspectives, planning for those needs, and ensuring that what is planned ultimately results in the intended outcomes (Step 1). Additionally, the CPM is structured to embrace the principles of leverage and reuse by assisting planners in determining whether there are other organizations that have previously addressed similar needs, and whether their business model, experiences and work products can be leveraged to expedite improvement (Step 2).

Ultimately, the CPM helps planners work with leadership and stakeholders to clearly articulate a roadmap that defines needs, what will be done to address those needs, when actions will be taken, how much it will cost, what benefits will be achieved, when those benefits will be achieved, and how those benefits will be measured (Step 3). The methodology also helps planners support leadership and stakeholders as they make decisions regarding which courses of action are appropriate for the mission, including specific investment and implementation decisions (Step 4). Finally and perhaps most importantly, the methodology provides planners with guidance in their support of measuring the actual performance changes that have resulted from the recommendations, and in turn, using these results in future planning activities (Step 5).

The five steps of the CPM are detailed as follows:

Step 1: Identify and Validate

Purpose: The purpose of this step is to identify and assess what needs to be achieved, understand the major drivers for change, and then define, validate, and prioritize the operational realities of the mission and goals with leadership, stakeholders, and operational staff. During this step, the leadership, stakeholder, and customer needs and the operational requirements are validated so that ultimately, all stakeholder groups are working towards the same, well understood, validated outcome. Initial performance metrics are created to begin focusing the measurement of success to be consistent across stakeholder groups. In this step, “leadership” can range in levels of scope from an executive leader over an international challenge to a functional leader who has identified steady state improvements that may include services, systems, or infrastructure. An additional purpose of this step is to identify and engage appropriate governance.

Architect’s Role: In this step, architects facilitate a direct collaboration between leadership and stakeholders as they work together to define, validate, and prioritize their needs, and build a shared vision and understanding. In doing so, the architects analyze stated needs in the context of overarching drivers to help aid decision makers in their assessment of whether stated needs are feasible and realistic. Since these needs shape the scope and strategic intent for planning, it is imperative that leadership and stakeholders agree on the needs before work begins on subsequent planning steps.

In addition to identifying needs, architects work with leadership and stakeholders to establish target performance metrics that will ultimately be used to determine if the planned performance has been achieved. Once needs are identified and validated, architects support leadership in identifying and initiating appropriate governance. Who makes the decisions and when those decisions will be made is important to the timing and buy-in of recommendations for change.

Outcome: At the end of Step 1, the key outcomes are (1) identified and validated needs, (2) an overarching set of performance metrics, and (3) a determination of who (governance) will ultimately oversee and approve recommended changes to meet those needs.

Step 2: Research and Leverage

Purpose: The purpose of this step is to identify external organizations and service providers that may have already met, or are currently facing needs similar to the ones identified in Step 1, and then to analyze their experiences and results to determine if they can be applied and leveraged or if a partnership can be formed to address the needs together. In alignment with “Shared First” principle, it is at this point that the planners consult both internal and external service catalogs for pre-existing services that are relevant to the current needs. In some instances, an entire business model, policy, technology solution, or service may be reusable to address the needs defined in Step 1 – an important benefit in these cost-constrained, quickly evolving times. Based on this analysis, leadership and stakeholders determine whether or not they will be able to leverage the experiences and results from other organizations.

Architect’s Role: Architects facilitate the research of other organizations and service providers to assess whether they have similar needs and whether these organizations have already met these needs or are currently planning to meet these needs. The architects lead the assessment of the applicability of the other organizations’ experiences and results and help to determine whether there are opportunities to leverage or work together to plan. Once these organizations and their needs and experiences have been identified and assessed, the architect formulates a set of findings and recommendations detailing the applicability and opportunity for leverage. These findings and recommendations are submitted to leadership who engages governance with this information as appropriate.

Outcome: At the conclusion of Step 2, the architects, leadership, and stakeholders have a clear grasp on the experiences and results of other organizations, and the leadership and / or governance have determined whether or not they can leverage these experiences for their own needs. In some instances, another organization may be currently planning for similar needs and a partnership can be formed to collectively plan for these needs. The decision to leverage or not leverage has a significant impact on the planning activities in Step 3. For instance, if the organization determines that its can leverage policies and systems from another organization in order to meet its own needs, these policies and systems become a critical input to planning in Step 3.

Step 3: Define and Plan

Purpose: The purpose of this step is to develop the integrated plan for the adjustments necessary to meet the needs identified in Step 1. Recommended adjustments could be within any or all of the architecture domains: strategy, business, data, applications, infrastructure, and security. The integrated plan defines what will be done, when it will be done, how much it will cost, how to measure success, and the significant risks to be considered. Additionally, the integrated plan includes a timeline highlighting what benefits will be achieved, when their completion can be expected, and how the benefits will be measured. It is during this step that analysis of current capabilities and environments results in recommended adjustments to meet the needs identified in Step 1. Also during this step, the formal design and planning of the target capabilities and environment is performed. In addition to the integrated plan, the full complement of architecture, capital planning, security, records, budget, human capital, and performance compliance documents is developed based on the analysis performed in Step 3. The end outcome is an integrated set of plans that can be considered and approved by leadership and governance.

Architect’s Role: Architects lead the development of the architecture by applying a series of analysis and planning methods and techniques. Through this process, the architects plan for each of the architecture domains (strategy, business, data, applications, infrastructure, and security) and produce data as well as artifacts to capture, analyze, and visualize the plans for change. Most important is the architect’s efforts to synthesize the planning into recommendations that can be considered and approved by leadership and governance. During the creation of the architecture, architects facilitate interaction with other planning disciplines (e.g. budget, CPIC, security) so that each discipline’s set of plans is integrated into a cohesive set of recommendations to meet the needs stated in Step 1. Throughout these efforts, architects maintain the integrated plan and roadmap to reflect the course of action that has been determined through these planning activities.

Outcome: At the end of Step 3, leadership and stakeholders will possess an integrated set of plans and artifacts defining what will be done, when it will be done, what benefits will be achieved and when, and an estimate of cost. This set of plans should be synthesized into discrete decision-making packages for leadership and governance that are appropriate given financial, political, and organizational constraints.

Step 4: Invest and Execute

Purpose: The purpose of this step is to make the investment decision and implement the changes as defined in the integrated plan. Many groups participate in this step, however, it is important to note that these groups will need to work as a coordinated and collaborative team to achieve the primary purpose of this step: to successfully implement the planned changes.

Architect’s Role: In this step the architect is in a support role, assisting in investment and implementation activities by providing information to aid in decisions, and to support interpretation and revision of plans from Step 3. The architects may be required to continue research and analysis into other organizations and their experiences (Step 2), update plans (Step 3), or re-engage stakeholders for feedback (Step 1). The architects have a continuing support role (e.g. interpreting the plans, making changes to the plans, supporting decision making) throughout investment and implementation. The involvement of architects does not cease at the conclusion of planning in Step 3.

Outcome: During Step 4, a decision is made concerning the investment in the changes that were planned in Step 3. At the end of Step 4 the recommendations for addressing the defined needs have been implemented. If the investment is not approved, the architect, leadership, and stakeholders return to previous steps to alter the recommendations and plans for future leadership consideration. It is important to reiterate that the integrated plans (Step 3) and the implementation (Step 4) could consist of a variety of changes to include, but not limited to, policy changes, organizational changes, technology changes, process changes, and skills changes.

Step 5: Perform and Measure

Purpose: During Step 5 the mission is operated with the new capabilities planned in Step 3 and implemented in Step 4. The purpose of Step 5 is to operate the mission and measure performance outcomes against identified metrics.

Architect’s Role: The architects may not be the keeper of the actual performance data, but they need to leverage available performance data to assess whether the implemented capabilities achieve planned performance metrics. Feedback from this step can feed into future planning efforts as well as immediate planning and implementation adjustments as necessary. Feedback may also necessitate more immediate changes in plans that may need to be considered by governance, including configuration management.

Outcome: At the end of Step 5, the new capabilities as planned in Step 3 and implemented in Step 4 will be operational. The key outcome of this step is measured performance outcomes against identified metrics.

Sub-Architecture Domains

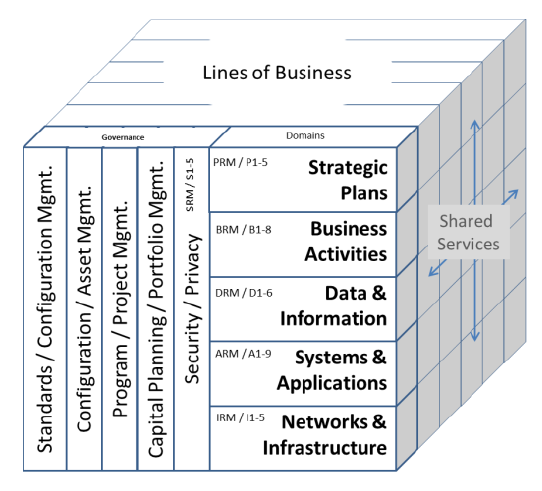

Each solution produces a tangible capability (e.g., system, network, service) that spans six sub-architectural domains in the overall EA: strategy, business, data, applications, infrastructure, and security. These domains are hierarchical (except security, which is a “thread” or cross cutting concern involving all domains) in that strategic goals drive business activities, which are the source of requirements for services, data flows, and technology enablement. Security controls pervade all of the other domains by providing risk-adjusted control elements in the form of hardware, software, policy, process, and physical solutions.

Using the Architected Solution

The value of having an EA and being able to implement an architected solution is that it produces one or more design alternatives and authoritative information to support planning and decision-making for mission and support requirements. EA provides standards, methodologies, and guidelines that architects can re-use for their designs and plans.

Importance of the Framework

An EA framework defines the scope of the architecture and the relationship of sub-architecture views to enable analysis, design, documentation, and reporting. There are a number of EA frameworks in use in the public and private sectors, and this guidance does not seek to require only one type, but there are characteristics that a framework should possess to be selected for use in the federal sector:

- Comprehensive: Covers all aspects of an agency through current and future views of the strategic, business, and technology areas at whatever level of scope is selected;

- Integrated: Shows the relationship between sub-architecture domains for strategy, business, data, applications, infrastructure, and security; and

- Scalable: Supports architecture practices at various levels of scope

The Federal EA Framework, version 2.0 (FEAF-II) meets these criteria, an example of which is provided in Figure 6 on the next page. The geometry of the FEAF-II shows the hierarchical relationship of the major areas of the architecture, which serves to emphasize that strategic goals drive business services, which in turn provide the requirements for enabling technologies. This framework also shows the relationship of sub-architecture domains, how the architecture can be decomposed into segments (that follow structural or functional lines in the organization) and how shared services would be positioned. Finally, FEAF-II correlates the other areas of governance (capital planning, program management, and human capital management); documentation via an enterprise-wide modernization roadmap, a standard set of core / elective artifacts and reporting via standard reference model taxonomies in each sub-architecture domain.

EA Basic Element #4: Tools

Various types of software applications (tools) are required to support EA documentation and analysis activities, including:

- Repository website and content to create a visual representation of architecture

- Decomposable views of the overall architecture and specific architectures

- Over-arching “management views” of the architecture

- Strategic planning products and performance measures

- Business process documentation to answer key questions and solve problems

- Physical and logical design of data entities, objects, applications, and systems

- Physical and logical design of networks & cloud computing environments

- Links to applications and databases for analysis and reporting

- Links to the portfolio of investments and asset inventory

- Configuration management and quality standards

- Security and risk solutions for physical, information, personnel and operational needs

The tools that an agency selects for use with an EA program should not only develop and store documentation, but must be data centric and meet stakeholder needs for information to support planning and decision-making.

In using architecture information to support planning and decision-making, the EA repository is intended to provide a single place for the storage and retrieval of architecture artifacts. Some of the artifacts are created using tools and some are custom developed for particular uses (e.g., composite management views). A repository works best if it is easy to access and use. For this reason, a web-based EA repository is recommended. A repository should be located on the internal network to provide security for the information while still supporting access by executives, managers, and staff.

EA Basic Element #5: Standards

Architectural standards apply to all areas of EA practice and are essential to achieving interoperability and resource optimization through common methods for analysis, design, documentation, and reporting. Standards are included in the common approach to federal EA from a number of authoritative sources that are non-proprietary and support the ability to develop and use architectures within and between federal organizations, at the state, tribal, local and international levels, and with industry partners. Without standards, EA models and analyses will be done differently and “likewise comparisons” will not be possible between systems, services, lines of business, and organizations. Selected standards should include those from leading bodies nationally and throughout the world, including the National Institute of Science and Technology (NIST), the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), the International Enterprise for Standardization (ISO), and the European Committee on Standardization (CEN).

EA artifacts are important standardization elements. An artifact is a type of model or documentation that describes part or all of an architecture. Types of artifacts include reports, diagrams, charts, tables, matrices, and spreadsheets. The format for high-level EA artifacts is often succinct text documents or diagrams that describe overall strategies, programs, and desired outcomes. Mid-level EA artifacts are documents, diagrams, charts, spreadsheets, and presentation slides that describe organizational processes, services, supply chains, systems, information flows, networks, and web sites. Low-level EA artifacts describe specific system and application resources, interface specifications, data dictionaries, technical standards, network hardware, and security controls. When these EA artifacts are harmonized and integrated to the greatest extent possible through the organizing taxonomy of the EA framework, new and more useful views of the architecture are generated. This is one of the greatest values of EA as a documentation process… creation of the ability to see a hierarchy of views of the organization and/or lines of business that can be examined from several perspectives.

A “Reference Architecture” is an authoritative source of information about a specific subject area that guides and constrains the instantiations of multiple architectures and solutions. Reference Architectures solve a specific (recurring) problem in a problem space; explain context, goals, purpose, and problem being solved including when and how Reference Architecture should be used; and provide concepts, elements and their relationships that are used to direct/guide and constrain the instantiation of repeated concrete solutions and architectures. Reference Architecture serves as a reference foundation for architectures and solutions and may also be used for comparison and alignment purposes. There may be multiple Reference Architectures within a subject area where each represents a different emphasis or viewpoint of that area. A Reference Architecture for one subject area can be a specialization of a more general Reference Architecture in another subject area. The level of abstraction provided in a Reference Architecture is a function of its intended usage.

In this guidance for the Common Approach to Federal EA, there is one core documentation artifact for each of the six sub-architecture views, which serves to promote consistent views within and between architecture as well as promoting interoperability within and between government organizations. Additional details are provided in the “Documentation” section.

EA Basic Element #6: Use

The value of EA is in both the process and the products. Doing an architecture project provides a focus on a mission or support area of the organization and the resulting analysis and design activities, if done correctly, support improvements in that area. Only an enterprise-wide architecture can provide an integrated view of strategic, business, and technology domains across all lines of business, services, and systems – which is key to optimizing mission capabilities and resource utilization. At present, there is no other management best practice, other than EA, that can serve as a context for enterprise-wide planning and decision making. When an EA is viewed as authoritative by agency leadership, then it becomes a catalyst for consistent methods of analysis and design, which are needed for the organization to remain agile and effective with limited resources.

EA Basic Element #7: Reporting

The reporting function of an EA program is important in maintaining an understanding of current capabilities and future options. Providing a repository of architecture artifacts, plans, solutions, and other information is not enough (a “pull” model). What is also needed is regular reporting on capabilities and options through the lens of the architecture, delivered in a standardized way and from dash-boards for overall progress and health (a “push” model). The primary products for this type of standardized reporting are two-fold: (1) an annual EA Plan, and (2) a set of reference models that contain taxonomies to categorize information consistently in each sub-architecture view, as well as for the overall architecture. These plans and reference models do not contain artifacts. They contain information about what is in an architecture to support consistent reporting as well as supporting planning, decision-making, and analysis activities.

EA Basic Element #8: Audit

Auditing architectures and EA programs is important to ensuring quality work, consistent methods, and increasing levels of capability and maturity. As with any management or technology program, periodic audits are needed by internal and external experts to ensure that proper methods are being followed, information is accurate, and value is being produced for the organization. Add audits and recommendations should be presented to the Agency CIO for review and action.

EA program and project auditing methods should be consistent with this common approach to federal EA and should also support the use of the EA Maturity Management Framework (EAMMF) Version 2.0 as a tool to evaluate maturity and promote the capability of EA programs.9 The EAMMF v2.0 consists of four critical success attributes for managing EA programs; 7 maturity stages; and 59 elements of EA management that are at the core of an EA program.

Content

- Overall Concept

- Primary Outcomes

- Levels of Scope

- Basic Elements of Federal Enterprise Architecture

- Documentation

- Reference Models

- Plans and Views

- Terms and Definitions

- References